I spent some time collecting nut samples from 24 different pecan cultivars to check on pecan scab infection levels. This season we applied 3 fungicide sprays to our pecan orchard. So when you look at the photos keep that in mind. Cultivars with zero scab lesions are either scab resistant or our scab control efforts were able to keep the disease in check. In many cases, the shucks of some pecan cultivar show signs of scab infection but the level of infection is not severe enough to impact nut size, kernel fill, or shuck opening. Peruque is an example of a cultivar that was not protected by our scab spray program and scab has engulfed the entire nut (photo above). Colby is scab susceptible but our scab control program limited the disease to a few small of scab lesions. Norton and Osage are scab resistant--the black spots on these shucks are the result of limb rub.

Major is a scab resistant cultivar (photo above). Kanza, Lakota, and Hark all have Major as one of their parents and are also scab free. Even though these four cultivars are scab resistant that does not mean that they are immune to all pecan diseases. The fungicides we applied to our grove this year have kept the shucks of Major and her daughters from contracting pecan anthracnose.

The photo above show four early-ripening northern pecan cultivars. Warren 346 and Lucas were completely clean showing zero scab lesions. In contrast, Mullahy and Goosepond had scab lesions despite our spray program.

Oswego is a seedling of Greenriver and both cultivars are scab resistant (Photo above). Posey and Surecrop are only slightly susceptible to scab and it appears that our spray program has prevented all disease on the shucks.

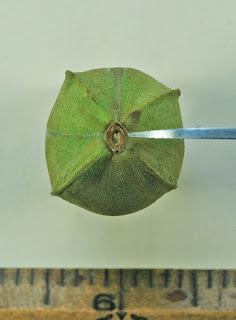

Giles is a cultivar selected from a native grove just 2 miles from our research station. Giles shows scab susceptibility despite our efforts to control the disease (photo above). Jayhawk and SWB617 have Giles parentage but Jayhawk is scab resistant. The scab resistance of Jayhawk must come from its unknown parent. Chetopa is another local cultivar, originating as a native tree at the Pecan Experiment Field. Chetopa is not scab resistant but three fungicide applications have kept this cultivar clean.

The final photo of cultivars show that Mandan, Pawnee, and Faith are all susceptible to pecan scab. Mohawk was free of the disease.

With the exception of Peruque, we have been able to control scab on susceptible cultivars to a point where we will see no economic losses. This year we invested about $60 per acre in disease controlling fungicide sprays. Judging from the crop I see on the trees, we should average over 1200 lbs. of pecans per acre. That more that enough nuts to pay for our spray costs.