Pecans are loved not only by millions of folks around the world but it seems that every critter in the great outdoors loves to feast on pecans too. One of the things we watch for when cleaning pecans are bird pecks (photo at right). Although crows are the best known avian pecan thieves, they tend to break open the entire nut with their massive bill, devour the entire kernel, and leave nothing behind but shell fragments.. On the other hand, woodpeckers and flickers seem to be nut samplers--pecking a hole through the shell, taking a few bites, dropping the nut to the ground, then searching for another nut to sample. These are the nuts we pick up with pecan harvest.

The cultivar Peruque, by far, is the pecan most susceptible to bird peck. The woodpeckers and flickers like Peruque because of its small (easy to carry) size and extremely thin shell. The top two nuts in the photo are Peruque. To a lesser degree, we find a lot of bird peck on large, thin-shelled cultivars like Shoshoni (nut at the bottom of photo), Maramec, and Mohawk.

Woodpeckers and flickers are federally protected "song birds" and can not be hunted, trapped or poisoned. The only way to minimize damage from bird peck is to harvest your crop a fast as you can.

Wednesday, November 23, 2011

Cracked pecan shells at harvest

If you have been following this blog over the last several months you might remember that a heavy rain in September saved our drought stricken pecan crop this year by promoting kernel fill. At that time, I warned that we might find that the pressure of an expanding kernel might actually crack the shell on nuts that had sized during the drought. By late September, I found one early maturing cultivar that was split open by the kernel. Now that we are in the middle of harvest and are cleaning pecans, we have noticed several cracked shells crossing the inspection table (photo at right).

The cracks we've observed in the shell have appeared both along the suture (middle nut above right) and 90 degrees to the suture (top nut above right). We even found a pecan cracked both ways (bottom nut above right). All of these cracks were created by a sudden expansion of kernel following the September down pour.

So far, we have seen significant shell cracking on the cultivars Colby, Hirschi, and Henning. In looking at kernels inside these cracked nuts it seems that, if a nut cracked along the suture, the kernel became discolored where tissues seem to pop out of the shell (middle nut above). When the shell is cracked 90 degrees to the suture, the kernel remained fully inside the shell and developed no discoloration (photo at left).

Cracks in the shell allow pathogens and insects easy access to pecan kernel. When we see these nuts on the cleaning table we discard them in order to maintain top quality in our final product.

The cracks we've observed in the shell have appeared both along the suture (middle nut above right) and 90 degrees to the suture (top nut above right). We even found a pecan cracked both ways (bottom nut above right). All of these cracks were created by a sudden expansion of kernel following the September down pour.

So far, we have seen significant shell cracking on the cultivars Colby, Hirschi, and Henning. In looking at kernels inside these cracked nuts it seems that, if a nut cracked along the suture, the kernel became discolored where tissues seem to pop out of the shell (middle nut above). When the shell is cracked 90 degrees to the suture, the kernel remained fully inside the shell and developed no discoloration (photo at left).

Cracks in the shell allow pathogens and insects easy access to pecan kernel. When we see these nuts on the cleaning table we discard them in order to maintain top quality in our final product.

Thursday, November 17, 2011

Why won't some pecan shucks split open?

We've been harvesting pecans this week and I've noticed quite a few green nuts still up in the trees. With this mornings low temperature registering 24 degrees F, all those green shucks were frozen and are quickly turning black. But long before last night's freeze, there was a reason those nuts where green and still stuck in the shuck (Photo above shows sticktights vs normal nut).

In a previous post, I described how pecan weevils can cause pecan shucks to remain green long after normal nuts have split shuck and started to dry. But the nuts pictured above remained green until last night's freeze and failed to open correctly because the kernel inside failed to develop.

Here is a photo of a well developed Kanza nut vs. a Kanza sticktight (photo at left). You can plainly see that the sticktight nut developed a seed coat but never filled it with kernel (read about kernel filling here). Since the seed coat is a normal tan color, we can assume that the lack of kernel filling was related to this past summer's drought. Under drought conditions, pecan trees often abort part of their nut crop to be able to fill the nuts that remain.

If the seed coat had been dark black inside, stinkbug feeding in early August would have been the cause for the lack of kernel development. In any case, it looks like we will have a lot of sticktights to pick off the cleaning table this fall.

In a previous post, I described how pecan weevils can cause pecan shucks to remain green long after normal nuts have split shuck and started to dry. But the nuts pictured above remained green until last night's freeze and failed to open correctly because the kernel inside failed to develop.

Here is a photo of a well developed Kanza nut vs. a Kanza sticktight (photo at left). You can plainly see that the sticktight nut developed a seed coat but never filled it with kernel (read about kernel filling here). Since the seed coat is a normal tan color, we can assume that the lack of kernel filling was related to this past summer's drought. Under drought conditions, pecan trees often abort part of their nut crop to be able to fill the nuts that remain.

If the seed coat had been dark black inside, stinkbug feeding in early August would have been the cause for the lack of kernel development. In any case, it looks like we will have a lot of sticktights to pick off the cleaning table this fall.

Tuesday, November 15, 2011

Oh deer!

I visited a pecan planting in Missouri last week to collect some nut samples. I didn't find any nuts but what I did find was well defined deer trails to each and every tree (photo above). Many city folks might not realize that Bambi loves feasting on pecans. I say.... "Eat more venison!"

Labels:

deer,

pecan pests

Spotting pecan weevil damage

Harvest time is here. By this time in November, all the shucks have split open and most are dried down to a deep chocolate brown revealing the pecan inside. However, you might spot some nuts that have tight, green shucks still hanging on the tree (photo at right). Unfortunately, those green nuts will never open.

Shuck split in pecan is controlled by plant growth regulators that are manufactured by the maturing seed inside the nut. If the kernel never forms or is devoured by a pecan weevil larva, the shucks will never open. These damaged pecans will remain green and tight on the tree until a hard freeze turns them into black "sticktights".

This year, I've seen green nuts caused by both summer drought and pecan weevil. The green nuts caused by drought are typically 1/2 normal size and contain only a wafer of kernel. Pecan weevil infested nuts are normal sized but have no kernel inside (consumed by weevil larvae). Pecan weevil damaged pecan are easily recognized by a round exit hole created by the larva (photo at left).

If you spot numerous pecan weevil damaged nuts in your trees this fall, you can be certain that pecan weevil will back with a vengeance in 2013 (pecan weevil has a 2 year life cycle).

Shuck split in pecan is controlled by plant growth regulators that are manufactured by the maturing seed inside the nut. If the kernel never forms or is devoured by a pecan weevil larva, the shucks will never open. These damaged pecans will remain green and tight on the tree until a hard freeze turns them into black "sticktights".

This year, I've seen green nuts caused by both summer drought and pecan weevil. The green nuts caused by drought are typically 1/2 normal size and contain only a wafer of kernel. Pecan weevil infested nuts are normal sized but have no kernel inside (consumed by weevil larvae). Pecan weevil damaged pecan are easily recognized by a round exit hole created by the larva (photo at left).

If you spot numerous pecan weevil damaged nuts in your trees this fall, you can be certain that pecan weevil will back with a vengeance in 2013 (pecan weevil has a 2 year life cycle).

Monday, November 7, 2011

Major's daughters

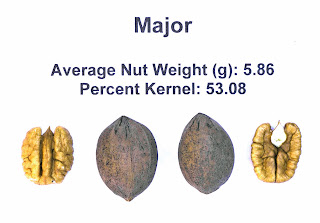

Over 100 years ago, a seedling pecan tree growing near the confluence of the Green and Ohio Rivers (in Kentucky) was discovered that would become the foundation of this century's most important northern pecan cultivars. Introduced in 1908, 'Major' quickly became known as a disease resistant pecan cultivar that produces quality kernels every year. Today, 'Major' is one of the old standards of the northern pecan industry.

In the years to come, the importance of 'Major' to northern pecan growers may change. 'Major' may become better know as the disease resistant parent of two important cultivars--Kanza and Lakota. Kanza resulted from a controlled cross of Major and Shoshoni, while Lakota has Mahan and Major parentage. Looking at all 3 nuts, you might not suspect Major as being a parent of both Kanza and Lakota. However, Major has transferred excellent pecan scab resistance to both progeny.

The other day I spent some time to inspect the crops held by many of the cultivars we have under test. As usual, our large 'Major' trees (30 yrs-old) had a decent crop of nuts. Just like the old timers say, you can always rely on 'Major' to produce nuts.

I then went on to inspect the crops set by Major's daughters--Kanza and Lakota. After a tremendous crop last year, Kanza has set a fair crop this year (photo at right). Kanza had us fooled most of the year because we didn't see many nuts in the lower portion of the canopy. Once the leaves started to fall, we spotted a good crop of Kanza nuts up in the tree tops. (This is the first indication we might need to thin our Kanza block).

Lakota (photo at left) also set a good crop of nuts in 2011. In fact, Lakota may have produced too many nuts for this drought-stricken, growing season. However, Lakota is like its Major parent. If water becomes limiting, the nuts become smaller but they still produce a quality kernel.

Over the next 10 to 15 years we will learn if the daughters of Major (Kanza & Lakota) become the reliable standards in which northern pecan growers can count on.

In the years to come, the importance of 'Major' to northern pecan growers may change. 'Major' may become better know as the disease resistant parent of two important cultivars--Kanza and Lakota. Kanza resulted from a controlled cross of Major and Shoshoni, while Lakota has Mahan and Major parentage. Looking at all 3 nuts, you might not suspect Major as being a parent of both Kanza and Lakota. However, Major has transferred excellent pecan scab resistance to both progeny.

The other day I spent some time to inspect the crops held by many of the cultivars we have under test. As usual, our large 'Major' trees (30 yrs-old) had a decent crop of nuts. Just like the old timers say, you can always rely on 'Major' to produce nuts.

I then went on to inspect the crops set by Major's daughters--Kanza and Lakota. After a tremendous crop last year, Kanza has set a fair crop this year (photo at right). Kanza had us fooled most of the year because we didn't see many nuts in the lower portion of the canopy. Once the leaves started to fall, we spotted a good crop of Kanza nuts up in the tree tops. (This is the first indication we might need to thin our Kanza block).

Lakota (photo at left) also set a good crop of nuts in 2011. In fact, Lakota may have produced too many nuts for this drought-stricken, growing season. However, Lakota is like its Major parent. If water becomes limiting, the nuts become smaller but they still produce a quality kernel.

Over the next 10 to 15 years we will learn if the daughters of Major (Kanza & Lakota) become the reliable standards in which northern pecan growers can count on.

Labels:

kanza,

lakota,

major,

pecan cultivars

Thursday, November 3, 2011

Waiting for harvest

Pecan leaves have turned golden yellow and are starting to fall from the trees (photo above). Our pecan shakers are all greased up and the broken fingers in our pecan harvesters have been replaced. In short, we are all ready to start the 2011 harvest season but the nuts just aren't ready yet.

Even though most shucks have been split for several weeks now, we still have too many green shucks to start harvest (photo at right). We could shake our trees today and the harvester would beat off the green shucks but the harvested nuts would be full of moisture. Wet nuts turn into moldy nuts and we can't afford to degrade the quality of the crop just because we are anxious to get the harvest started.

we are anxious to get the harvest started.

If you pull off one of the green shucks, you can actually see moisture trapped between the nut and shuck (photo below right). A pecan will not dry completely until the shuck has turn dark brown and lost all its moisture. A good hard freeze (26 degrees F or below) is what we really need. Cold temepratures would kill the remaining green tissues in the shuck and allow both shuck and nut to dry quickly.

Even though most shucks have been split for several weeks now, we still have too many green shucks to start harvest (photo at right). We could shake our trees today and the harvester would beat off the green shucks but the harvested nuts would be full of moisture. Wet nuts turn into moldy nuts and we can't afford to degrade the quality of the crop just because

we are anxious to get the harvest started.

we are anxious to get the harvest started. If you pull off one of the green shucks, you can actually see moisture trapped between the nut and shuck (photo below right). A pecan will not dry completely until the shuck has turn dark brown and lost all its moisture. A good hard freeze (26 degrees F or below) is what we really need. Cold temepratures would kill the remaining green tissues in the shuck and allow both shuck and nut to dry quickly.

Labels:

pecan harvest

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)