Monday, February 20, 2017

Thinning more Kanza trees

For the past six years, we have been progressively thinning a three acre block of Kanza trees. This week, we removed trees within the Kanza block in areas where adjacent trees were competing for sunlight and according to our thinning plan (photo above). During this sixth year of thinning, we cut down 15 trees; the most we've removed in a single year. The original tree planting had 144 Kanza trees. After removing 15 trees this year, we'll be down to 96 trees in the orchard. The first thinning will be complete when half the trees have been removed and we are down to 72 trees in the 3 acre orchard.

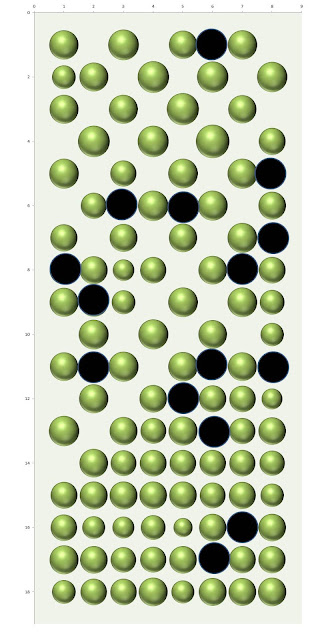

The figure at right is a map of the Kanza block as it appeared before we cut any trees this winter. Each tree is depicted by a green circle with a diameter proportional to the tree's trunk diameter. As you can see, tree growth has not been even across this orchard. Tree growth has been fastest in the northern 1/3 of the orchard. As a result, we've thinned more trees in this area of the orchard. However, trees in the southern half of the orchard continue to grow and will require thinning eventually.

We removed 15 trees from the Kanza Block this year. Trees cut down are marked by black circles on the map at right. We thinned trees over the entire planting but most removed trees were located in the middle third of the orchard.

Up to this point, I've been pleased with this progressive approach to orchard thinning. By taking out trees on an as-needed basis, we have been able to maintain good light penetration into the orchard while preserving high yields.

Thursday, February 16, 2017

Pecan tree limb pruning and collecting scions

On a mild sunny days in February, its hard for me to stay indoors when there are pecan trees to prune and scionwood to collect. When approaching a young tree, like the one pictured at right, I confine my pruning efforts to removing low limbs and removing serious structural problems. And, because I'm pruning young trees, the limbs I cut off usually produce some excellent scionwood. Let me take you through the process.

I started by removing the lowest limb on the left side of the tree pictured above. When removing low limbs, always cut back to the trunk but make that cut outside the branch bark collar.

The photo above shows the tree before and after pruning. The side limb I removed looks like it was growing out of a socket in the main trunk. The raised bark area on the trunk that forms that socket is what we call the branch bark collar. I plunged the blade of my chainsaw into the side of the limb just outside the collar and dropped the limb off the tree. Leaving the branch collar intact will help the tree quickly heal over the wound.

I moved over to the other side of the tree to prune off the next lowest limb on the tree. With this limb, the branch bark collar is not so obvious. In the photo at right you can see a slight swelling of the bark around the limb where it attaches to the trunk. The place to prune off the limb is marked by the red dashed line. The final cut is shown on the far right.

My goal in pruning off lower limbs is to make working around the tree easier. In the photo at right, you can see that removing just two limbs makes a big difference in terms of improving access for orchard operations like mowing, herbicide application and harvest.

Besides cutting off lower limbs, my dormant season pruning routine also includes looking for potential structural problems. One common problem is the development of a V crotch (circled in yellow in photo at right). Left to grow, a V crotch will form a bark inclusion between the two branches increasing the likelihood of branch tear out. So while the tree is still relatively small, I reached up and cut off one of the two branches that had formed the V. After taking out the V crotch the tree might look unbalanced but it will quickly fill the open space in the canopy with new shoot growth.

I also look to remove branches with narrow crotch angles and deep bark inclusions. The method I use to cut out these narrow angled branches depends on the size of the limb. Previously, I showed you how I cut out a larger limb using the three cut method. With the 2.5 inch side limb pictured above I made just 2 cuts. The first cut I made was and undercut about 1/3 the way through the branch. I made this cut at an angle that would promote rapid wound healing. Next I used the chainsaw to plunge cut into the side of the limb to remove the limb.

The young trees I pruned were growing rapidly so the branched I removed held many one-year-old shoots that were over 2 feet long. Before hauling the pruned limbs off to the brush pile, I cut off any shoot that wase 3/8 inch or larger in diameter. Some of the wood I collected is shown at right.

In collecting scions, make sure to collect only last year's shoot growth. Sometimes on young trees its a little difficult to tell where 2-year wood stops and 1-year wood begins. In the photo at left, the yellow arrow points to the annual growth ring which is the point on a shoot that marks the beginning of a new shoot growth year. Above the growth ring is 1-year wood. Note the large primary buds on the 1-year shoots. Below the growth ring is 2-year wood. Note that the primary buds on 2-year wood are gone. They either dropped off the tree or sprouted last year to produce catkins. Either way scionwood without strong buds is useless.

In cutting scions, I usually cut the wood into 7 to 8 inch long pieces, making sure I have at least 2 good buds on the upper half of the scion. In cutting up the wood, I also like to make sure the lower half of the scion is straight. Looking at the shoot pictured at above I noticed a strong curve at the base of the shoot. I cut off the curved portion of the shoot and discarded it. Right above the curve I cut out a perfect piece of Kanza scion.

In cutting scions, I also look for scars or imperfections in the wood. Since I'm collecting scions from low limbs, I find that some branches get banged up by the tractor when I mow the orchard. I always cut out imperfections like one pictured at left. There is usually plenty of good scions to be found above and below such a branch wound.

I started by removing the lowest limb on the left side of the tree pictured above. When removing low limbs, always cut back to the trunk but make that cut outside the branch bark collar.

The photo above shows the tree before and after pruning. The side limb I removed looks like it was growing out of a socket in the main trunk. The raised bark area on the trunk that forms that socket is what we call the branch bark collar. I plunged the blade of my chainsaw into the side of the limb just outside the collar and dropped the limb off the tree. Leaving the branch collar intact will help the tree quickly heal over the wound.

I moved over to the other side of the tree to prune off the next lowest limb on the tree. With this limb, the branch bark collar is not so obvious. In the photo at right you can see a slight swelling of the bark around the limb where it attaches to the trunk. The place to prune off the limb is marked by the red dashed line. The final cut is shown on the far right.

My goal in pruning off lower limbs is to make working around the tree easier. In the photo at right, you can see that removing just two limbs makes a big difference in terms of improving access for orchard operations like mowing, herbicide application and harvest.

Besides cutting off lower limbs, my dormant season pruning routine also includes looking for potential structural problems. One common problem is the development of a V crotch (circled in yellow in photo at right). Left to grow, a V crotch will form a bark inclusion between the two branches increasing the likelihood of branch tear out. So while the tree is still relatively small, I reached up and cut off one of the two branches that had formed the V. After taking out the V crotch the tree might look unbalanced but it will quickly fill the open space in the canopy with new shoot growth.

I also look to remove branches with narrow crotch angles and deep bark inclusions. The method I use to cut out these narrow angled branches depends on the size of the limb. Previously, I showed you how I cut out a larger limb using the three cut method. With the 2.5 inch side limb pictured above I made just 2 cuts. The first cut I made was and undercut about 1/3 the way through the branch. I made this cut at an angle that would promote rapid wound healing. Next I used the chainsaw to plunge cut into the side of the limb to remove the limb.

The young trees I pruned were growing rapidly so the branched I removed held many one-year-old shoots that were over 2 feet long. Before hauling the pruned limbs off to the brush pile, I cut off any shoot that wase 3/8 inch or larger in diameter. Some of the wood I collected is shown at right.

In collecting scions, make sure to collect only last year's shoot growth. Sometimes on young trees its a little difficult to tell where 2-year wood stops and 1-year wood begins. In the photo at left, the yellow arrow points to the annual growth ring which is the point on a shoot that marks the beginning of a new shoot growth year. Above the growth ring is 1-year wood. Note the large primary buds on the 1-year shoots. Below the growth ring is 2-year wood. Note that the primary buds on 2-year wood are gone. They either dropped off the tree or sprouted last year to produce catkins. Either way scionwood without strong buds is useless.

In cutting scions, I usually cut the wood into 7 to 8 inch long pieces, making sure I have at least 2 good buds on the upper half of the scion. In cutting up the wood, I also like to make sure the lower half of the scion is straight. Looking at the shoot pictured at above I noticed a strong curve at the base of the shoot. I cut off the curved portion of the shoot and discarded it. Right above the curve I cut out a perfect piece of Kanza scion.

In cutting scions, I also look for scars or imperfections in the wood. Since I'm collecting scions from low limbs, I find that some branches get banged up by the tractor when I mow the orchard. I always cut out imperfections like one pictured at left. There is usually plenty of good scions to be found above and below such a branch wound.

Tuesday, February 14, 2017

Kanza yield 2016

As most readers of this blog will know, I am a big fan of the Kanza pecan (photo at right). At the Pecan Experiment Field we have a 3 acre block of Kanza trees that was established when we planted nuts in the field to produce rootstock trees back in 1996. These seedling trees were then grafted to Kanza during the years 2000-2003. The original planting contained 144 trees but since 2012 we have been removing trees as adjacent trees start to crowd. My goal was to maintain a high level of nut production while preventing tree over-crowding. I outlined this gradual thinning plan in a blog post back in 2012.

By 2016, we have removed 33 trees, yet total yield per acre has increased (table below). Yield was negatively affected in 2011 and 2012 by intense summer droughts and small nut size.

We saw the first indication of Kanza over-producing in 2016, so I expect a drop off in yield in 2017. In addition, I've marked 15 trees in the Kanza block for removal this winter. Can the remaining trees make up for the lost production from thinned trees? I guess we'll find out come next fall.

By 2016, we have removed 33 trees, yet total yield per acre has increased (table below). Yield was negatively affected in 2011 and 2012 by intense summer droughts and small nut size.

We saw the first indication of Kanza over-producing in 2016, so I expect a drop off in yield in 2017. In addition, I've marked 15 trees in the Kanza block for removal this winter. Can the remaining trees make up for the lost production from thinned trees? I guess we'll find out come next fall.

Tuesday, February 7, 2017

Pruning top-worked pecan trees

Back in 2014, I decided to top-work some young trees to new cultivars. In previous posts, I wrote about the grafting process and training those new grafts. Because these trees were fairly large when I placed a bark graft on the central leader, I left several lower limbs on the tree to provide critical leaf area to keep the tree actively growing. For the past 3 growing seasons, I've pruned back the growth on limbs below the graft to encourage growth of the new scion (graft union painted white--photo at right). At this point, the tree's new top has begun to fill out and I can safely start removing limbs below the graft union.

The tree pictured above was easy to prune. I simply removed the two largest low limbs (photo at left). This left me with a couple of small diameter limbs under the graft union but I'll leave those on for now. One of the disadvantages of top-working a tree this size is how quickly it grows in height. It becomes increasingly difficult to train a central leader 15 feet up in the air. As the new growth begins to burst forth this spring, I'll get out my 8 foot orchard ladder and practice some directive pruning on the top of this tree.

The next top-worked tree I needed to prune presented more of a challenge (photo at right). This tree had four strongly growing limbs growing under the graft union (graft union painted white). In fact, it looks like the lower side limbs are actively competing with the scion and slowing the growth of the new top.

The problem with this tree is that 3 of the 4 limbs growing below the graft union are attached to the trunk adjacent to each other (photo above left). Pruning all these limbs off at one time would leave almost two thirds of the trunk's diameter without bark--limiting the ability of the tree to transport nutrients to the scion. I decided to remove just two of the limbs this year (cuts marked by yellow dashed lines). I'll let the tree callus over these two wounds before I remove the remaining limbs under the graft.

To help further promote the growth of the scion, I pruned back some of the growth on the remaining low limbs (photo at left). Then, over the course of the summer, I'll continue pruning back the side limbs that are growing out from below the graft.

The one large side limb I left on the tree will definately try to outgrowth the scion. It will take monthly summer-pruning sessions to keep this limb in check. By mid-summer, I'll probably have this limb cut back to half its current length. In one or two years, the entire limb will be removed back to the trunk.

The tree pictured above was easy to prune. I simply removed the two largest low limbs (photo at left). This left me with a couple of small diameter limbs under the graft union but I'll leave those on for now. One of the disadvantages of top-working a tree this size is how quickly it grows in height. It becomes increasingly difficult to train a central leader 15 feet up in the air. As the new growth begins to burst forth this spring, I'll get out my 8 foot orchard ladder and practice some directive pruning on the top of this tree.

The next top-worked tree I needed to prune presented more of a challenge (photo at right). This tree had four strongly growing limbs growing under the graft union (graft union painted white). In fact, it looks like the lower side limbs are actively competing with the scion and slowing the growth of the new top.

The problem with this tree is that 3 of the 4 limbs growing below the graft union are attached to the trunk adjacent to each other (photo above left). Pruning all these limbs off at one time would leave almost two thirds of the trunk's diameter without bark--limiting the ability of the tree to transport nutrients to the scion. I decided to remove just two of the limbs this year (cuts marked by yellow dashed lines). I'll let the tree callus over these two wounds before I remove the remaining limbs under the graft.

To help further promote the growth of the scion, I pruned back some of the growth on the remaining low limbs (photo at left). Then, over the course of the summer, I'll continue pruning back the side limbs that are growing out from below the graft.

The one large side limb I left on the tree will definately try to outgrowth the scion. It will take monthly summer-pruning sessions to keep this limb in check. By mid-summer, I'll probably have this limb cut back to half its current length. In one or two years, the entire limb will be removed back to the trunk.

Friday, February 3, 2017

Pecan yields from a native grove

Many readers of this blog are interested in planting new orchards of grafted pecan trees. However, Southeast Kansas is blessed to have thousands of acres of mature native pecan trees growing in the flood plains of major rivers (photo above). The proper care of these seedling trees helps to fill the niche market for small, sweet, oily kernels that are the perfect size for fitting on top of cookies, pies, and cakes.

At the Pecan Experiment Field we have been recording pecan production from native trees for over 35 years. Each year, we harvest the pecans from six half-acre plots. The chart above illustrates the fluctuations in yield we have observed over the past eleven years (click on the chart to enlarge). I chose this time period so you can see how I trees responded following two catastrophic weather events that impacted our native trees. In 2007, the Easter freeze killed emerging pecan buds and destroyed 3/4 of all our pistillate blossoms. The impact on yield was dramatic. Then in December of 2007, we suffered an ice storm that ended up breaking about half the limbs off our trees. Pecan yield in 2008 and 2009 suffered. After 2 years of vigorous shoot regrowth, the trees returned to normal yields in 2010 (1157 lbs/acre is our 35 year average). Since 2010, native pecan yield hit a high in 2012 and failed to impress in 2015. We've basically returned to a normal level of yield fluctuation. I wonder how our natives will bear in 2017. Only time will tell.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)