After some warm days and some much needed rain, pecan trees are finally starting to show a burst of new growth this week (photo at right). When you see new leaves just starting to unfurl, the tree is giving you the signal that it is the best time to start bark grafting.

For an in-depth look at the bark grafting method I use to top-work pecan trees, check out this previous post. In today's post, I wanted to show you how I attack the top-working process while giving a few tips along the way.

The tree I chose to top-work was a beautiful example of a well trained tree that had previously been grafted to Jayhawk (photo at left). Over the past several years we have noticed some serious kernel quality issues with Jayhawk so I decided to regraft this tree to a selection from our pecan breeding program.

My first cut was on the central leader about 18 inches above the lowest whorl of side branches. This cut is marked by the uppermost red line. I also removed a small side limb on the left side of the tree just below the cut I made on the central leader. I also removed the upward-growing portion of a lateral branch on the right side of the tree to make sure my new graft will get plenty of light. These cuts are also marked by red lines on the photo.

The photo at left shows you how the tree looks after I finished pruning. Notice how open the center of the tree looks. This openness will allow full sun to reach the graft and will promote rapid regrowth. Although chopped back to one half its original height, the central leader still holds a prominent position in this tree's architecture. Leaving 18 inches of central leader above lower branches will help draw energy and nutrients toward the new graft and increase the chances for graft success.

Now let's focus our attention on selecting the location to insert a bark graft. After cutting the central leader, I looked at the shape of the cut stump (photo at right). Notice how the left side of the stump seems to have a flat spot and is not as highly curved as the rest of the stem. This is where I will place my graft.

I then inspected the health of the bark on the flat side of the trunk. Right within the grafting zone I found a prominent bud scar (in yellow circle at left). I have often found that the cambium layer under this kind of bud scar is dead causing the bark to adhere to the wood making scion insertion difficult. In addition, a dead zone in the cambium of the stock within the grafting zone limits overall graft success.

In this case, I was able to make the incision in the bark far enough to the right of the bud scar to avoid any potential problems. After carving the scion, I inserted it between the bark and wood of the stock and slid it into position perfectly.

The photo at right shows the scion in place and the bark flap stapled tightly against scion's cut surfaces. Note that I was able to avoid sliding the scion under any portion of the bud scar. Time to wrap the graft union in aluminum foil and cover with a plastic bag.

Before leaving this newly top-worked tree, I attached a bamboo stake to the trunk of the tree (photo at left). The stake will provide a bird perch to prevent bird damage to the scion. As the new graft emerges, I can then tie the new shoots to the stake to prevent wind damage. Last but not least, I labeled the tree with the name of the scion cultivar.

When I moved on to the next Jayhawk tree, I found a not-so-perfectly-shaped tree (photo at right). At first glance the tree was growing every-which-way. The tree had at least one "V" crotch that I had tried to suppress in previous years with pruning. As soon as I approached this tree, I knew this tree was going to need some major pruning along with my planned top-working.

As I came in closer to look at the tree limb structure, I quickly noticed a major limb wound on the main trunk. I also found no clear place to position a bark graft so it would grow without direct competition from lateral limbs. This tree was going to need radical pruning.

I then decided to remove most of the upper portions of this tree. My first cut was to remove entire left side (larger diameter side) of the tree's forked trunk. The smoother bark and smaller diameter of the right side fork would provide a perfect grafting spot once the limb was stubbed back. Fortunately, this tree a several small, lateral branches growing out of the trunk below my pruning cuts. These branches would help shade the trunk and prevent any sunscald that might occur following such radical pruning.

My neighbors are sure going to shake their heads when they drive by this tree (photo at right). Some might even think I was trying to kill the tree. However, once I insert a new scion and that scion takes off this summer, I will have a graft that will grow tall and straight providing me a great central leader tree.

The photo at left shows the branch stub that will receive my scion. As I said before, I like to place the graft on the flat side of the stock. When grafting forked trees, I have always noticed that the flattest side will be facing the inside of the fork. That is exactly where I inserted the scion in this tree.

The completed graft is shown below.

Tuesday, April 29, 2014

Friday, April 25, 2014

Pecan trees restart growth after frost

A little rain and some warm temperatures have prompted our pecan trees to resume budbreak (photo at right). This week I've spent a lot of time looking at levels of freeze damage have have come to four conclusions.

A little rain and some warm temperatures have prompted our pecan trees to resume budbreak (photo at right). This week I've spent a lot of time looking at levels of freeze damage have have come to four conclusions.1. Trees that had expanding leaves and exposed catkins on April 15 were hardest hit by the freeze.

2. Cultivar origin had little impact on severity of cold injury. Worst hit cultivars included Hennings (a far northern cultivar) and Maramec ( a southern pecan).

3. Frost damage much worse on lower branches.

4. Frost damage varies widely within a tree; from branch to branch and from bud to bud.

Let me show you some examples of how our trees are responding to the April 15 freeze.

The photo above shows three branch terminals all growing from a single larger branch of the USDA clone 64-11-17. The shoot in the middle appears to be growing normally with no apparent cold injury. The shoot on the right has a green terminal bud but mid-shoot buds look frozen and not greening up. The shoot on the left looks totally damaged by the frost. This is the kind of wide variation in cold injury we are seeing throughout the grove.

The photo at left illustrates the variation we are finding in bud injury on a single shoot. The terminal bud of this Chetopa shoot was fully killed by the freeze. Just below is a vegetative bud that suffered freeze injury to its outer scales but the growing point remained unfrozen. The surviving growing point is now emerging to create new leaves. Other buds on this shoot look to be developing normally while still others appear frozen. Have enough buds survived to produce enough new shoots, pistillate flowers and catkins to produce a decent crop this year? We will be watching closely in the weeks to come.

Labels:

bud break,

cold injury

Wednesday, April 16, 2014

Frost damage and tree height

The frost that settled over the Neosho River floodplain Tuesday morning was a so-called radiation frost. These type of frosts occur on clear, calm

nights when the earth radiates heat back into the atmosphere. During a

radiation frost the temperature near the soil surface will be colder

than temperatures higher up in the canopies of pecan trees. The temperature gradient that is created by a radiation freeze can end up creating a distinctive kill line in the canopy of pecan trees. Buds below the kill line are exposed to temperatures capable of killing green tissue. Above the kill line, temperatures are slightly higher and pecan buds can escape damage. Yesterday, I used our hydraulic lift to see if I could find evidence of a kill line.

My first stop was a Greenriver tree. From the ground, I could tell that this cultivar had suffered major freeze injury. Bud development was well advanced making the exposed green tissues very susceptible to cold. Since my hydraulic lift limits me to reaching just 25 feet above the ground, I decided to collect samples at 12 and 25 feet. Looking at the branches I collected from thee two heights, it looks like Greenriver was damaged well up into the tree's canopy (photo at right).

It wasn't until I cut open the terminal bud of these branches that I found that height does indeed impact the amount of cold injury. At 12 feet above the ground the emerging vegetative bud is nearly all black (photo at right). At 25 feet, you can see that the outer portion of the new shoot was burned but the inner core remained green. In looking at these buds it became clear to me that the bud at 12 feet was exposed to killing temperatures for a much longer time period than the bud at 25 feet. This make sense because as the earth looses it's heat to the night sky, the critical kill temperature line creeps higher with time. Then suddenly the sun pops out, air temperature rapidly increase and the freezing of plant tissue ceases.

I also looked at Kanza. Buds at both 12 and 25 feet looked in pretty good shape. Buds at the outer scale split stage of development may not be as cold resistant as fully dormant buds but they are far more cold hardy than buds that have started to elongate (like the Greenriver buds above). The real test would come when I split them open with a razor blade.

In the photo below, you can see that Kanza buds taken from both heights are still nice and green. Looks like our Kanza trees will be largely unaffected by this freeze.

My first stop was a Greenriver tree. From the ground, I could tell that this cultivar had suffered major freeze injury. Bud development was well advanced making the exposed green tissues very susceptible to cold. Since my hydraulic lift limits me to reaching just 25 feet above the ground, I decided to collect samples at 12 and 25 feet. Looking at the branches I collected from thee two heights, it looks like Greenriver was damaged well up into the tree's canopy (photo at right).

It wasn't until I cut open the terminal bud of these branches that I found that height does indeed impact the amount of cold injury. At 12 feet above the ground the emerging vegetative bud is nearly all black (photo at right). At 25 feet, you can see that the outer portion of the new shoot was burned but the inner core remained green. In looking at these buds it became clear to me that the bud at 12 feet was exposed to killing temperatures for a much longer time period than the bud at 25 feet. This make sense because as the earth looses it's heat to the night sky, the critical kill temperature line creeps higher with time. Then suddenly the sun pops out, air temperature rapidly increase and the freezing of plant tissue ceases.

I also looked at Kanza. Buds at both 12 and 25 feet looked in pretty good shape. Buds at the outer scale split stage of development may not be as cold resistant as fully dormant buds but they are far more cold hardy than buds that have started to elongate (like the Greenriver buds above). The real test would come when I split them open with a razor blade.

In the photo below, you can see that Kanza buds taken from both heights are still nice and green. Looks like our Kanza trees will be largely unaffected by this freeze.

Labels:

bud break,

cold injury

Tuesday, April 15, 2014

Freezing temperatures injure emerging pecan buds

During the pre-dawn hours of April 15th, temperatures dropped to 26 degrees F at the Pecan Experiment Field. At 26 degrees and lower rapidly expanding green pecan tissue is frozen and killed. A few trees had already developed visible catkins and were pushing out the first new leaves on new shoots. These trees were frozen back completely (photo at right). Fortunately, most trees had hardly started to push out new growth and escaped the freezing temperatures with little or no damage.

To really appreciate the extent of freeze damage we suffered Tuesday morning, I spent some time up in our hydraulic lift to survey bud health. Let's take a look.

The first thing I noticed was an amazing degree of variation within a single tree's canopy. Just look at the photo at left. These two branches are growing on the same Greenriver tree and are even attached to each other a few inches below the view of the photo. The branch on the left is fully green and shows no indication of cold injury while the branch on the right was burned by the frost. Why or how this happened has no easy explanation.

However, lets look at the kinds of variation I found within the canopies of some other trees to see if we can learn how this weather event will effect the 2014 pecan crop.

I stopped at the original Chetopa tree to see how the emerging buds looked. Once again, I found everything from healthy green buds to obviously dead buds (photo at right). Fortunately, the number of green buds on the Chetopa tree far outnumbered the damaged buds.

You can check the condition of your buds by slicing through a bud with a knife or razor blade. Healthy buds will be green while frost killed buds will be black (photo at right).

When I looked at a random native tree, I found similar variation in frost injury (photo at left). Once again I cut open some buds to check on their viability. However this time I found something fascinating.

Once again, the healthy buds were green inside while the frozen buds were black. However, look carefully at the bud in the middle of the photo. This bud, like all terminal pecan buds, comes in three parts. The center vegetative bud is flanked by two, catkin-containing sexual buds. In the photo, the sexual buds are black inside, indicating they were killed by the cold. However, the central vegetative bud is still green indicating live tissue. It will be interesting to follow all our tree over the next several weeks to see how the April 15th freeze impacts pecan flowing in May.

To really appreciate the extent of freeze damage we suffered Tuesday morning, I spent some time up in our hydraulic lift to survey bud health. Let's take a look.

The first thing I noticed was an amazing degree of variation within a single tree's canopy. Just look at the photo at left. These two branches are growing on the same Greenriver tree and are even attached to each other a few inches below the view of the photo. The branch on the left is fully green and shows no indication of cold injury while the branch on the right was burned by the frost. Why or how this happened has no easy explanation.

However, lets look at the kinds of variation I found within the canopies of some other trees to see if we can learn how this weather event will effect the 2014 pecan crop.

I stopped at the original Chetopa tree to see how the emerging buds looked. Once again, I found everything from healthy green buds to obviously dead buds (photo at right). Fortunately, the number of green buds on the Chetopa tree far outnumbered the damaged buds.

You can check the condition of your buds by slicing through a bud with a knife or razor blade. Healthy buds will be green while frost killed buds will be black (photo at right).

When I looked at a random native tree, I found similar variation in frost injury (photo at left). Once again I cut open some buds to check on their viability. However this time I found something fascinating.

Once again, the healthy buds were green inside while the frozen buds were black. However, look carefully at the bud in the middle of the photo. This bud, like all terminal pecan buds, comes in three parts. The center vegetative bud is flanked by two, catkin-containing sexual buds. In the photo, the sexual buds are black inside, indicating they were killed by the cold. However, the central vegetative bud is still green indicating live tissue. It will be interesting to follow all our tree over the next several weeks to see how the April 15th freeze impacts pecan flowing in May.

Labels:

bud break,

cold injury

Friday, April 11, 2014

Watching pecan bubreak

The past couple of days have been sunny and warm. Pecan buds are swelling and I have even noticed the early stages of catkin development. Today, I collected terminal branches from Kanza and Major to show you how bud development differs between protogynous (type 2) and protandrous (type 1) cultivars.

Back in 2012, I photographed some terminal branches that had already started vegetative shoot elongation. By that time, the differences between cultivars that shed pollen early (type 1) and those that shed late (type 2) were very obvious. The photo I took today shows pecan growth at a much earlier stage of development (photo above, right). Here the differences between protandrous and protogynous cultivars are a little more subtle.Let take a closer look.

The shoot on the right was cut from a Major pecan tree. Once the outer scale splits opens and falls off you will see what looks like 3 buds inside (see red arrow). The bud in the center will develop into a new vegetative shoot that will eventually terminate in a cluster of female flowers. The green buds that flank the central bud will develop into catkins. Note how plump and large the catkin producing buds are on the Major twig as compared to the thin, less-noticeable, catkin-containing buds that surround the vegetative bud on Kanza. To produce pollen early in the flowering season, Major catkins need to start developing early, starting right at bud break. In fact, the yellow arrow points to Major catkins starting to emerge from under the inner bud scale.

In comparison, late-pollen-shedding Kanza will expend most of its early growth energy creating new shoots capable of producing mature pistillate flowers quickly and ready to receive early flying pollen. Catkins will develop on Kanza at a much slower pace and will not begin to shed pollen until after pistillate flowers have pollinated by a protandrous cultivar like Major.

Back in 2012, I photographed some terminal branches that had already started vegetative shoot elongation. By that time, the differences between cultivars that shed pollen early (type 1) and those that shed late (type 2) were very obvious. The photo I took today shows pecan growth at a much earlier stage of development (photo above, right). Here the differences between protandrous and protogynous cultivars are a little more subtle.Let take a closer look.

The shoot on the right was cut from a Major pecan tree. Once the outer scale splits opens and falls off you will see what looks like 3 buds inside (see red arrow). The bud in the center will develop into a new vegetative shoot that will eventually terminate in a cluster of female flowers. The green buds that flank the central bud will develop into catkins. Note how plump and large the catkin producing buds are on the Major twig as compared to the thin, less-noticeable, catkin-containing buds that surround the vegetative bud on Kanza. To produce pollen early in the flowering season, Major catkins need to start developing early, starting right at bud break. In fact, the yellow arrow points to Major catkins starting to emerge from under the inner bud scale.

In comparison, late-pollen-shedding Kanza will expend most of its early growth energy creating new shoots capable of producing mature pistillate flowers quickly and ready to receive early flying pollen. Catkins will develop on Kanza at a much slower pace and will not begin to shed pollen until after pistillate flowers have pollinated by a protandrous cultivar like Major.

Wednesday, April 9, 2014

Grinding out stumps

Over the past few weeks we have been thinning trees to give the remaining trees in our pecan orchards more room to grow. Even though we can cut the tree stump down fairly close to the soil surface with a chainsaw, that chunk of solid wood that still sticks up can still play havoc with our mowers.

Yesterday, we brought out our stump grinder to cut all our tree stump down to a level about 3 inches below the soil surface (photo above). Ours is a 3-point hitch model stump grinder that uses a spinning saw blade to grind the wood into chips. Hydraulic cylinders move the blade's arm up and down, back and forth, and right to left.

It takes about 5 minutes to grind down a 10-12 inch diameter pecan tree stump. Later this year, we will need to move soil into the hole that becomes noticeable after the remaining portion of the tree's root system starts to rot.

Yesterday, we brought out our stump grinder to cut all our tree stump down to a level about 3 inches below the soil surface (photo above). Ours is a 3-point hitch model stump grinder that uses a spinning saw blade to grind the wood into chips. Hydraulic cylinders move the blade's arm up and down, back and forth, and right to left.

It takes about 5 minutes to grind down a 10-12 inch diameter pecan tree stump. Later this year, we will need to move soil into the hole that becomes noticeable after the remaining portion of the tree's root system starts to rot.

Friday, April 4, 2014

Spring fertilizer application

After a couple of warm days our pecan trees have finally started to wake up. With the first signs of bud break, we decided to make our regular springtime application of nitrogen and potassium today (photo above). We applied 150 lbs/acre Urea and 100 lbs./acre Potash. In elemental form that equals 69 lbs/acre N and 60 lbs/acre K. Total cost of the application including spreader rent was $60.97/acre.

Thursday, April 3, 2014

Pecan buds showing signs of growth

Our pecan trees have been waiting all spring from some warm over-night temperatures to signal the arrival of a new growing season. Well, we had two warm nights in a row and today we spotted the first signs of bud development. I collected twigs from several cultivars to photograph and found most trees in the outer scale split stage (Warren 346, Kanza, and Greenriver). The red arrows in the photo at right points to buds with a split outer scale. In contrast, we found that Lakota buds had already shed the outer scale completely (black arrow). Colby, on the other hand was still completely dormant.

In normal years, cultivars with southern ancestry usually break bud before cultivars that have originated in the north. However, this year, it looks like budbreak is going to be unpredictable. Warren 346 is a far northern cultivar and it is breaking bud right along with Kanza and Greenriver. Lakota and Kanza share the same northern cultivar parent (Major) but Lakota is sightly ahead of Kanza.

This year's bud break picture becomes even more unusual when I found that our hickories are still dormant while pecans have started to push (photo at left). In the normal scheme of things, hickories and hicans (pecan/hickory hybrids) break bud 7 to 10 days before pecan. This year might become one of those rare years when hickory and pecan development coincides close enough to allow natural inter-genetic cross pollination. You never know, a new hican might arise from a seed pollinated in 2014.

In normal years, cultivars with southern ancestry usually break bud before cultivars that have originated in the north. However, this year, it looks like budbreak is going to be unpredictable. Warren 346 is a far northern cultivar and it is breaking bud right along with Kanza and Greenriver. Lakota and Kanza share the same northern cultivar parent (Major) but Lakota is sightly ahead of Kanza.

This year's bud break picture becomes even more unusual when I found that our hickories are still dormant while pecans have started to push (photo at left). In the normal scheme of things, hickories and hicans (pecan/hickory hybrids) break bud 7 to 10 days before pecan. This year might become one of those rare years when hickory and pecan development coincides close enough to allow natural inter-genetic cross pollination. You never know, a new hican might arise from a seed pollinated in 2014.

Wednesday, April 2, 2014

Pecan pruning answers

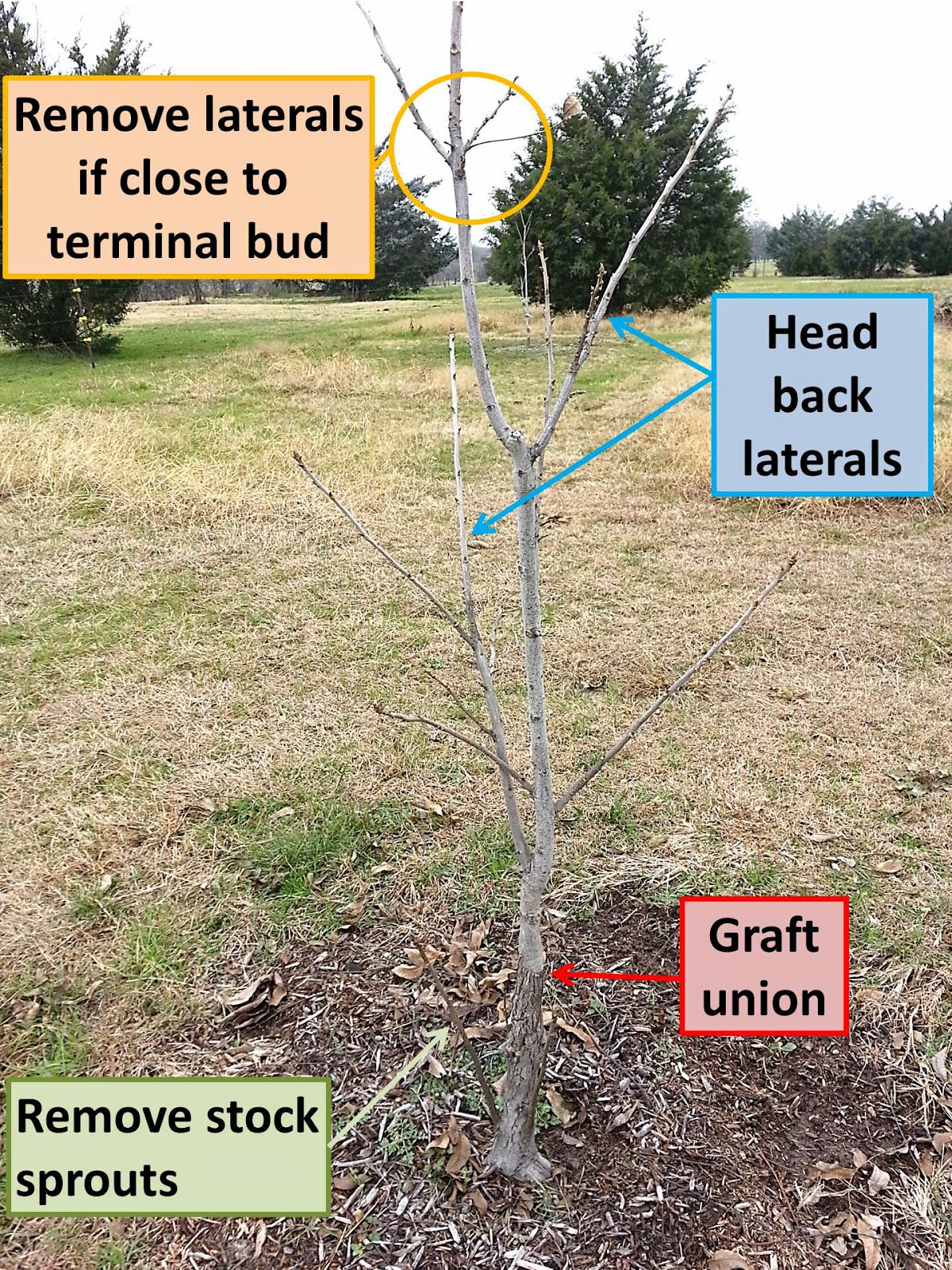

Its truly amazing that we live in an age when it is so easy for folks to take a digital photograph of their pecan tree and email that picture to me with their pruning and tree training questions. The photo at right is one such photo. Of course the photo came with the usual question--"How should I prune this tree?".

What's even more amazing are the software tools I have on my computer that allows me to edit the digital picture I receive and turn it into an neat instructional aid. I can usually enhance visual clarity of the photo then add words and arrows to point out recommended pruning cuts.

The photo at right is the same exact shot as the one shown above. I used photoshop to edit the photo then moved the image powerpoint to add graphics. Now lets talk about pruning. I'll start at the top. If those three small lateral branches within the orange circle are within two feet of the tree's apex, I'd remove them completely (the two foot rule) to preserve the dominance of the central leader. Next, I would head back the two strongly growing laterals (blue arrows) by pruning them back to either an outward growing side shoot or outward growing bud.

You can clearing see the change in bark texture that marks the site of the graft union (red arrow). Below the graft, you can barely make out a stock sprout. Remove this sprout entirely.

The owner of this young tree was also concerned about how to prune the "branches" at the base of the tree (photo at left). These are not branches but are exposed roots. Judging from what I see of the root system I can tell this young tree was originally grown in a container and the tree should have been set 2-3 inches deeper into the soil. However, now that the tree has become established, I would simply trim off those two small roots and leave the bigger exposed roots alone. In time, the tree will grow in trunk diameter and the exposed roots will seemingly disappear.

This photo of a back yard pecan tree was sent to me from South Africa (at left). The owner of this tree wanted to know the best way to prune this tree to a single trunks without tearing up the bark. Judging from the photo, this is a grafted pecan tree (graft union at the base of the tree) and its most likely the cultivar, Wichita.

Wichita is widely available in South Africa and the profusion of narrow angled branch connections as seen in the upper portion of the photo is characteristic of this cultivar. I'm going to let the tree's owner decide which side of the tree to keep, because in the end it won't really matter to the tree. With that said, I'd probably choose to remove the right fork because when I cut the limb it would have an open space to fall. Cutting the left side would mean placing a large limb on top of the garden wall.

Removing a large limb from a tree is a three cut process (graphic above). In cutting off a large limb you are removing a lot of weight and that falling weight can lead wood splintering or bark pealing. To control the limb removal process, start by making an undercut about 1/3 way through the branch at a point about one foot away from the trunk (cut 1 above). Next, start cutting from the upper side of the limb about one inch further out from the trunk (cut 2 above). Keep cutting until you start hearing wood crack. Stand back and watch the limb snap off the tree under it own weight. Now, with most of the weight pruned off, remove the branch stub just outside the branch collar (cut 3 above). If the limb crotch is wide enough for your chainsaw, you can make the final cut from the top downward. For narrow crotches, the final cut with the chainsaw will have to be from the bottom up. For folks experienced in using a chainsaw and know how to avoid saw kick-back, I generally use a plunge cut from the side to remove any angle branch stub.

My final pruning example comes from Texas. This back yard Choctaw pecan tree looks to be growing every direction but upwards (photo at left). For backyard trees is important to remember that the tree doesn't need to look textbook perfect; the tree will still make shade and nuts however it is mistreated. However, it is probably a good idea to make a couple of cuts on this tree just to give the tree a more balanced appearance and to encourage a central leader.

The lowest side limb on this tree is extremely vigorous and seems to be almost as large as the central leader (red arrow). To promote growth of the main trunk, this limb should be cut back . I've marked the place to cut with a short red. Note that this one cut will remove the upward growing portion of this side limb. What's left is less vigorous and outward growing. In removing this limb, I would use the 3 cut method described above in order to avoid possible bark damage to the remaining portion of the limb.

The yellow arrow points to a side limb that is directly competing with the central leader. The cut I would make here is shown by the short yellow line. Once again, I would remove an upward growing branch pruning it back to outward growing limb.

What's even more amazing are the software tools I have on my computer that allows me to edit the digital picture I receive and turn it into an neat instructional aid. I can usually enhance visual clarity of the photo then add words and arrows to point out recommended pruning cuts.

The photo at right is the same exact shot as the one shown above. I used photoshop to edit the photo then moved the image powerpoint to add graphics. Now lets talk about pruning. I'll start at the top. If those three small lateral branches within the orange circle are within two feet of the tree's apex, I'd remove them completely (the two foot rule) to preserve the dominance of the central leader. Next, I would head back the two strongly growing laterals (blue arrows) by pruning them back to either an outward growing side shoot or outward growing bud.

You can clearing see the change in bark texture that marks the site of the graft union (red arrow). Below the graft, you can barely make out a stock sprout. Remove this sprout entirely.

The owner of this young tree was also concerned about how to prune the "branches" at the base of the tree (photo at left). These are not branches but are exposed roots. Judging from what I see of the root system I can tell this young tree was originally grown in a container and the tree should have been set 2-3 inches deeper into the soil. However, now that the tree has become established, I would simply trim off those two small roots and leave the bigger exposed roots alone. In time, the tree will grow in trunk diameter and the exposed roots will seemingly disappear.

This photo of a back yard pecan tree was sent to me from South Africa (at left). The owner of this tree wanted to know the best way to prune this tree to a single trunks without tearing up the bark. Judging from the photo, this is a grafted pecan tree (graft union at the base of the tree) and its most likely the cultivar, Wichita.

Wichita is widely available in South Africa and the profusion of narrow angled branch connections as seen in the upper portion of the photo is characteristic of this cultivar. I'm going to let the tree's owner decide which side of the tree to keep, because in the end it won't really matter to the tree. With that said, I'd probably choose to remove the right fork because when I cut the limb it would have an open space to fall. Cutting the left side would mean placing a large limb on top of the garden wall.

Removing a large limb from a tree is a three cut process (graphic above). In cutting off a large limb you are removing a lot of weight and that falling weight can lead wood splintering or bark pealing. To control the limb removal process, start by making an undercut about 1/3 way through the branch at a point about one foot away from the trunk (cut 1 above). Next, start cutting from the upper side of the limb about one inch further out from the trunk (cut 2 above). Keep cutting until you start hearing wood crack. Stand back and watch the limb snap off the tree under it own weight. Now, with most of the weight pruned off, remove the branch stub just outside the branch collar (cut 3 above). If the limb crotch is wide enough for your chainsaw, you can make the final cut from the top downward. For narrow crotches, the final cut with the chainsaw will have to be from the bottom up. For folks experienced in using a chainsaw and know how to avoid saw kick-back, I generally use a plunge cut from the side to remove any angle branch stub.

My final pruning example comes from Texas. This back yard Choctaw pecan tree looks to be growing every direction but upwards (photo at left). For backyard trees is important to remember that the tree doesn't need to look textbook perfect; the tree will still make shade and nuts however it is mistreated. However, it is probably a good idea to make a couple of cuts on this tree just to give the tree a more balanced appearance and to encourage a central leader.

The lowest side limb on this tree is extremely vigorous and seems to be almost as large as the central leader (red arrow). To promote growth of the main trunk, this limb should be cut back . I've marked the place to cut with a short red. Note that this one cut will remove the upward growing portion of this side limb. What's left is less vigorous and outward growing. In removing this limb, I would use the 3 cut method described above in order to avoid possible bark damage to the remaining portion of the limb.

The yellow arrow points to a side limb that is directly competing with the central leader. The cut I would make here is shown by the short yellow line. Once again, I would remove an upward growing branch pruning it back to outward growing limb.

Labels:

pruning

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)