Friday, December 30, 2011

2011 Native pecan yields

For over 30 years, we have harvested native pecans from 6 one-half acre plots in an effort to create a historical record of nut production from well managed trees. After cleaning pecans for nearly 2 weeks straight, the yield data from these native plots has been recorded. The plots averaged 1294 lbs./acre in 2011. The lowest yielding plot produced at the rate of 866 lbs./ac while the highest yielding plot made 1910 lbs./ac. These same plots averaged 1286 lbs./ac last year (2010).

Here's a chart of yields from our native plots over the last 10 years. As noted on the graph, the 2007 crop was limited by the Easter Freeze which destroyed most emerging new shoots and the pistillate flowers contained in those shoots. The 2008 crop was limited by the December 2007 ice storm that broke nearly 50% of the limbs off our native trees. After 2 years of strong vegetative growth (2008 and 2009), our native trees have begun to bear at pre-2007 levels. It will be interesting to see how our trees react next year, following the stress of the 2011 drought.

Wednesday, December 28, 2011

Pecan harvest patterns

The pull-type picker has become the mainstay of the native pecan industry (photo at right). The other day, I drove past two native pecan groves and noticed huge differences in the pattern of leaves left on the ground after being blown out the back of the harvester.

In the first grove, you can see a distinctive circle of brushed grass around each tree with all the tree leaves scattered around the outside of the circle (photo at right). This grower picked each tree individually, starting at the dripline of a tree and working towards the trunk in a circular path.

In the second grove, the leaves were left in long rows, indicating the the harvesters were driven in a straight line, weaving around trees as they harvested large blocks of trees at a time (photo at right). In this case, the grove was picked much like you would mow the orchard floor. You start on the outside of the grove and work your way towards the middle of the field.

There is not a right or wrong way to harvest nuts. Both of these harvest patterns seem to work. However, at the Experiment Field, we tend to harvest our native trees in blocks rather than individual trees. Driving around in circles tends to make the operator crazy and I feel like the harvester can capture a wider swath of ground by driving a straighter path.

These photos also illustrate one very important difference between these two groves. Note the amount of leaves left behind after harvesting. The grove harvested in circles had far fewer leaves on the ground than the grove harvested as a block (the grove with more leaves). These two groves are adjacent to each other but only the second grove receives annual applications of nitrogen fertilizer. Regular nitrogen fertilization stimulates the growth of more leaves, more leaves capture more solar energy, and more energy in the tree results in more nuts.

Before harvest you could see an obvious difference in nut production between these two groves. After harvest the leaves tell the same story.

In the first grove, you can see a distinctive circle of brushed grass around each tree with all the tree leaves scattered around the outside of the circle (photo at right). This grower picked each tree individually, starting at the dripline of a tree and working towards the trunk in a circular path.

In the second grove, the leaves were left in long rows, indicating the the harvesters were driven in a straight line, weaving around trees as they harvested large blocks of trees at a time (photo at right). In this case, the grove was picked much like you would mow the orchard floor. You start on the outside of the grove and work your way towards the middle of the field.

There is not a right or wrong way to harvest nuts. Both of these harvest patterns seem to work. However, at the Experiment Field, we tend to harvest our native trees in blocks rather than individual trees. Driving around in circles tends to make the operator crazy and I feel like the harvester can capture a wider swath of ground by driving a straighter path.

These photos also illustrate one very important difference between these two groves. Note the amount of leaves left behind after harvesting. The grove harvested in circles had far fewer leaves on the ground than the grove harvested as a block (the grove with more leaves). These two groves are adjacent to each other but only the second grove receives annual applications of nitrogen fertilizer. Regular nitrogen fertilization stimulates the growth of more leaves, more leaves capture more solar energy, and more energy in the tree results in more nuts.

Before harvest you could see an obvious difference in nut production between these two groves. After harvest the leaves tell the same story.

Thursday, December 22, 2011

Stratifying pecan seeds

If you have even considered growing pecan trees from seed, the nuts will need to go through a process called stratification before they will germinate properly. Stratification is a simple process that involves soaking dry seed in water then storing that wet seed in a cool moist condition for 90 to 120 days. With stratification we are basically mimicking what happens in nature. A squirrel buries a pecan in the soil during the fall where it remains cool and moist all winter long. The squirrel-planted seed doesn't germinate until the following spring when the danger of frost has past.

Here's how I stratify pecans for next year's planting. First, I place new-crop nuts in a plastic container, filling it about 1/2 way. I then fill the box with enough water to cover the seeds and let the seeds soak overnight (photo at right). You will need to stir the nuts around in the water once in a while so the nuts on top don't dry.

After soaking. I add a moisture holding media to the nuts and water. In the past I've used peat moss, cedar shavings, potting soil or saw dust. This year I had plenty of saw dust on hand, so I mixed the dry saw dust into the nut and water mix (photo at right). I used enough sawdust to surround the nuts and soak up much of the free water. I let the saw dust soak up the moisture for a few hours then pored off any excess free water out of the box. I then placed the tight-fitting lid on the box and placed the box in the refrigerator.

For the stratification process to work effectively, the nuts should be held in cold storage at between 32 and 40 F (typical refrigerator temps). For northern pecan cultivars, germination is more uniform when nuts are held a full 120 days in stratification. By stratifying nuts now, you will have nuts ready for planting by May 1st, a perfect time for planting pecan seeds.

Here's how I stratify pecans for next year's planting. First, I place new-crop nuts in a plastic container, filling it about 1/2 way. I then fill the box with enough water to cover the seeds and let the seeds soak overnight (photo at right). You will need to stir the nuts around in the water once in a while so the nuts on top don't dry.

After soaking. I add a moisture holding media to the nuts and water. In the past I've used peat moss, cedar shavings, potting soil or saw dust. This year I had plenty of saw dust on hand, so I mixed the dry saw dust into the nut and water mix (photo at right). I used enough sawdust to surround the nuts and soak up much of the free water. I let the saw dust soak up the moisture for a few hours then pored off any excess free water out of the box. I then placed the tight-fitting lid on the box and placed the box in the refrigerator.

For the stratification process to work effectively, the nuts should be held in cold storage at between 32 and 40 F (typical refrigerator temps). For northern pecan cultivars, germination is more uniform when nuts are held a full 120 days in stratification. By stratifying nuts now, you will have nuts ready for planting by May 1st, a perfect time for planting pecan seeds.

Wednesday, December 21, 2011

Crows are a major pecan pest

| |

| A couple of crows high in pecan trees |

It is estimated that a single crow can consume 15 pounds of pecans per month. Crows will knock nuts to the ground, hold the pecan between their feet, and crack open the shell with their large, heavy beak. After cracking the nut open, they pick out the kernel, leaving shell and packing material on the ground.

|

| Pecan shells left after crow feeding |

Crows have become an increasing problem for pecan growers ever since they became federally protected bird--a result of the NAFTA treaty (the crow is the national bird of Mexico). Later this winter, we will be holding a meeting with Federal and State wildlife managers to develop an action plan for reducing crow populations. Watch this blog for further details as we make plans for this meeting.

Thursday, December 15, 2011

Watch for old pecans gathered at harvest

Here's a photo of three pecans we picked up with the harvester this fall. You might recognize these nuts as being all from the same cultivar--Kanza. The light colored nut on the right is from this year's crop, while the other 2 nuts were left behind from the 2010 crop. One of the things we look to remove from the cleaning table are old nuts that usually appear as dark reddish black nuts (nut pictured in the center). After sitting on the ground an entire year, these nuts become rancid and/or moldy.

We missed the moldy nut on the far left on the cleaning table only to find it later in a batch of cracked nuts. Look at the shell that still remains on the moldy nut. Its darker than the new crop nut but doesn't have that oil soaked appearance of the nut pictured in the middle. With thousands of nuts moving across the cleaning table, it easy to see how we missed pulling the moldy nut (before it was cracked) out of our 2011 crop.

I find it remarkable that pecans missed at harvest can survive an entire year out in the field without being discovered by squirrels, mice, crows, woodpeckers, insects and even deer. However, every year we find just a few old nuts come racing across the cleaning table that need to be thrown in trash pile.

We missed the moldy nut on the far left on the cleaning table only to find it later in a batch of cracked nuts. Look at the shell that still remains on the moldy nut. Its darker than the new crop nut but doesn't have that oil soaked appearance of the nut pictured in the middle. With thousands of nuts moving across the cleaning table, it easy to see how we missed pulling the moldy nut (before it was cracked) out of our 2011 crop.

I find it remarkable that pecans missed at harvest can survive an entire year out in the field without being discovered by squirrels, mice, crows, woodpeckers, insects and even deer. However, every year we find just a few old nuts come racing across the cleaning table that need to be thrown in trash pile.

Wednesday, December 14, 2011

Pecan harvest 2011

|

| Sonja raking sticks off the orchard floor |

While shaking our trees, I started thinking about area farmers that have spent most of harvest season complaining about a lack of nuts in their groves. One guy even argued that the cold temperatures we had last February (-17 F) were the reason he didn't have a crop. But when confronted by the fact that the Experiment Field was producing nuts in 2011, he simply stated that a dome of warm temperatures protected the trees just east of Chetopa. Talk about hot air!

|

| Darrell harvesting pecans |

Pesticides are another major input for pecan producers. This year we invested $42.63/acre in insecticides and fungicides. We sprayed for casebearer and scab in June, stinkbug and weevil in August, and weevil in September. This year's dry summer helped prevent the spread of pecan scab. As a result, our fungicide applications were kept to a bare minimum and we were able to save a little money.

|

| Cracked pecans |

Saturday, December 3, 2011

Fewer black spots on kernels in 2011.

Its not until you crack open a sample of this year's pecan crop do you discover the level of damage created by stink bug feeding. As I mentioned in an earlier post, the black spots found on pecan kernels are the result of feeding by stinkbugs and/or leaf-footed bugs (photo at right).

Last year (2010) we found quite a bit of stink bug damage. This year (2011) the number of kernels with black spots are far fewer. I wish I could come up with a good explanation for the year-to-year variation in stink bug damage but it turns out that the movements and population numbers for this group of plant feeding bugs are very hard to predict.

Over the past several years, our control strategy for kernel feeding bugs has been to apply an insecticide (Warrior II) in early August. Subsequent insecticide applications aimed at pecan weevil also help decrease stink bug populations. These control measures are not perfect but seem to keep kernel damage down to less that 1% of kernels.

Last year (2010) we found quite a bit of stink bug damage. This year (2011) the number of kernels with black spots are far fewer. I wish I could come up with a good explanation for the year-to-year variation in stink bug damage but it turns out that the movements and population numbers for this group of plant feeding bugs are very hard to predict.

Over the past several years, our control strategy for kernel feeding bugs has been to apply an insecticide (Warrior II) in early August. Subsequent insecticide applications aimed at pecan weevil also help decrease stink bug populations. These control measures are not perfect but seem to keep kernel damage down to less that 1% of kernels.

Thursday, December 1, 2011

Ice storm recovery update

Its been 4 years since the pecan groves around Chetopa,Kansas were hit by a massive ice storm. Once the leaves have fallen from the trees you can still see the scars of limb breakage left behind in the canopies of our trees. In the photo at right, you can see that vigorous new shoots have developed where limbs were torn from the tree by the weight of the ice. With each passing year, our trees are filling out their canopies, increasing the area where nuts can be produced.

But where are the nuts? It seems that the native pecan trees that did not set nuts on undamaged limbs, didn't set a crop on the new shoots either. In contrast, native trees that did set a crop (photo at left) produced pecans on both old and new branches. What we are seeing at this point is that the new shoots developed in response to ice-induced limb loss are now fully mature (able to produce a nut crop) and synchronized with the entire tree.

If you take a closer look at the regrowth associated with ice-storm-related limb breakage, you can see that an over-abundance of new shoots have developed in many areas (photo at right). Note that these vigorous branches have also developed numerous lateral shoots. As the trees continue to grow, competition for sunlight among these new shoots will eventually lead to the natural thinning of the most heavily shaded limbs (the so called self pruning process).

Squirrel damage has also led to some much needed limb thinning on ice-damaged trees. I've been shaking trees this harvest season only to find several branches that have developed since the ice storm on the ground (photo left). Note the dried leaves still attached to the shoot indicating that this shoot was injured by squirrels last summer.

If you look at the base of the shoot you can clearly see that the bark had been stripped back by squirrels feeding on the cambial layer of the shoot. A combination of summer winds and harvest tree shaking snapped these dead shoots out of the tree.

But where are the nuts? It seems that the native pecan trees that did not set nuts on undamaged limbs, didn't set a crop on the new shoots either. In contrast, native trees that did set a crop (photo at left) produced pecans on both old and new branches. What we are seeing at this point is that the new shoots developed in response to ice-induced limb loss are now fully mature (able to produce a nut crop) and synchronized with the entire tree.

If you take a closer look at the regrowth associated with ice-storm-related limb breakage, you can see that an over-abundance of new shoots have developed in many areas (photo at right). Note that these vigorous branches have also developed numerous lateral shoots. As the trees continue to grow, competition for sunlight among these new shoots will eventually lead to the natural thinning of the most heavily shaded limbs (the so called self pruning process).

Squirrel damage has also led to some much needed limb thinning on ice-damaged trees. I've been shaking trees this harvest season only to find several branches that have developed since the ice storm on the ground (photo left). Note the dried leaves still attached to the shoot indicating that this shoot was injured by squirrels last summer.

If you look at the base of the shoot you can clearly see that the bark had been stripped back by squirrels feeding on the cambial layer of the shoot. A combination of summer winds and harvest tree shaking snapped these dead shoots out of the tree.

Wednesday, November 23, 2011

Birds love pecans too!

Pecans are loved not only by millions of folks around the world but it seems that every critter in the great outdoors loves to feast on pecans too. One of the things we watch for when cleaning pecans are bird pecks (photo at right). Although crows are the best known avian pecan thieves, they tend to break open the entire nut with their massive bill, devour the entire kernel, and leave nothing behind but shell fragments.. On the other hand, woodpeckers and flickers seem to be nut samplers--pecking a hole through the shell, taking a few bites, dropping the nut to the ground, then searching for another nut to sample. These are the nuts we pick up with pecan harvest.

The cultivar Peruque, by far, is the pecan most susceptible to bird peck. The woodpeckers and flickers like Peruque because of its small (easy to carry) size and extremely thin shell. The top two nuts in the photo are Peruque. To a lesser degree, we find a lot of bird peck on large, thin-shelled cultivars like Shoshoni (nut at the bottom of photo), Maramec, and Mohawk.

Woodpeckers and flickers are federally protected "song birds" and can not be hunted, trapped or poisoned. The only way to minimize damage from bird peck is to harvest your crop a fast as you can.

The cultivar Peruque, by far, is the pecan most susceptible to bird peck. The woodpeckers and flickers like Peruque because of its small (easy to carry) size and extremely thin shell. The top two nuts in the photo are Peruque. To a lesser degree, we find a lot of bird peck on large, thin-shelled cultivars like Shoshoni (nut at the bottom of photo), Maramec, and Mohawk.

Woodpeckers and flickers are federally protected "song birds" and can not be hunted, trapped or poisoned. The only way to minimize damage from bird peck is to harvest your crop a fast as you can.

Cracked pecan shells at harvest

If you have been following this blog over the last several months you might remember that a heavy rain in September saved our drought stricken pecan crop this year by promoting kernel fill. At that time, I warned that we might find that the pressure of an expanding kernel might actually crack the shell on nuts that had sized during the drought. By late September, I found one early maturing cultivar that was split open by the kernel. Now that we are in the middle of harvest and are cleaning pecans, we have noticed several cracked shells crossing the inspection table (photo at right).

The cracks we've observed in the shell have appeared both along the suture (middle nut above right) and 90 degrees to the suture (top nut above right). We even found a pecan cracked both ways (bottom nut above right). All of these cracks were created by a sudden expansion of kernel following the September down pour.

So far, we have seen significant shell cracking on the cultivars Colby, Hirschi, and Henning. In looking at kernels inside these cracked nuts it seems that, if a nut cracked along the suture, the kernel became discolored where tissues seem to pop out of the shell (middle nut above). When the shell is cracked 90 degrees to the suture, the kernel remained fully inside the shell and developed no discoloration (photo at left).

Cracks in the shell allow pathogens and insects easy access to pecan kernel. When we see these nuts on the cleaning table we discard them in order to maintain top quality in our final product.

The cracks we've observed in the shell have appeared both along the suture (middle nut above right) and 90 degrees to the suture (top nut above right). We even found a pecan cracked both ways (bottom nut above right). All of these cracks were created by a sudden expansion of kernel following the September down pour.

So far, we have seen significant shell cracking on the cultivars Colby, Hirschi, and Henning. In looking at kernels inside these cracked nuts it seems that, if a nut cracked along the suture, the kernel became discolored where tissues seem to pop out of the shell (middle nut above). When the shell is cracked 90 degrees to the suture, the kernel remained fully inside the shell and developed no discoloration (photo at left).

Cracks in the shell allow pathogens and insects easy access to pecan kernel. When we see these nuts on the cleaning table we discard them in order to maintain top quality in our final product.

Thursday, November 17, 2011

Why won't some pecan shucks split open?

We've been harvesting pecans this week and I've noticed quite a few green nuts still up in the trees. With this mornings low temperature registering 24 degrees F, all those green shucks were frozen and are quickly turning black. But long before last night's freeze, there was a reason those nuts where green and still stuck in the shuck (Photo above shows sticktights vs normal nut).

In a previous post, I described how pecan weevils can cause pecan shucks to remain green long after normal nuts have split shuck and started to dry. But the nuts pictured above remained green until last night's freeze and failed to open correctly because the kernel inside failed to develop.

Here is a photo of a well developed Kanza nut vs. a Kanza sticktight (photo at left). You can plainly see that the sticktight nut developed a seed coat but never filled it with kernel (read about kernel filling here). Since the seed coat is a normal tan color, we can assume that the lack of kernel filling was related to this past summer's drought. Under drought conditions, pecan trees often abort part of their nut crop to be able to fill the nuts that remain.

If the seed coat had been dark black inside, stinkbug feeding in early August would have been the cause for the lack of kernel development. In any case, it looks like we will have a lot of sticktights to pick off the cleaning table this fall.

In a previous post, I described how pecan weevils can cause pecan shucks to remain green long after normal nuts have split shuck and started to dry. But the nuts pictured above remained green until last night's freeze and failed to open correctly because the kernel inside failed to develop.

Here is a photo of a well developed Kanza nut vs. a Kanza sticktight (photo at left). You can plainly see that the sticktight nut developed a seed coat but never filled it with kernel (read about kernel filling here). Since the seed coat is a normal tan color, we can assume that the lack of kernel filling was related to this past summer's drought. Under drought conditions, pecan trees often abort part of their nut crop to be able to fill the nuts that remain.

If the seed coat had been dark black inside, stinkbug feeding in early August would have been the cause for the lack of kernel development. In any case, it looks like we will have a lot of sticktights to pick off the cleaning table this fall.

Tuesday, November 15, 2011

Oh deer!

I visited a pecan planting in Missouri last week to collect some nut samples. I didn't find any nuts but what I did find was well defined deer trails to each and every tree (photo above). Many city folks might not realize that Bambi loves feasting on pecans. I say.... "Eat more venison!"

Spotting pecan weevil damage

Harvest time is here. By this time in November, all the shucks have split open and most are dried down to a deep chocolate brown revealing the pecan inside. However, you might spot some nuts that have tight, green shucks still hanging on the tree (photo at right). Unfortunately, those green nuts will never open.

Shuck split in pecan is controlled by plant growth regulators that are manufactured by the maturing seed inside the nut. If the kernel never forms or is devoured by a pecan weevil larva, the shucks will never open. These damaged pecans will remain green and tight on the tree until a hard freeze turns them into black "sticktights".

This year, I've seen green nuts caused by both summer drought and pecan weevil. The green nuts caused by drought are typically 1/2 normal size and contain only a wafer of kernel. Pecan weevil infested nuts are normal sized but have no kernel inside (consumed by weevil larvae). Pecan weevil damaged pecan are easily recognized by a round exit hole created by the larva (photo at left).

If you spot numerous pecan weevil damaged nuts in your trees this fall, you can be certain that pecan weevil will back with a vengeance in 2013 (pecan weevil has a 2 year life cycle).

Shuck split in pecan is controlled by plant growth regulators that are manufactured by the maturing seed inside the nut. If the kernel never forms or is devoured by a pecan weevil larva, the shucks will never open. These damaged pecans will remain green and tight on the tree until a hard freeze turns them into black "sticktights".

This year, I've seen green nuts caused by both summer drought and pecan weevil. The green nuts caused by drought are typically 1/2 normal size and contain only a wafer of kernel. Pecan weevil infested nuts are normal sized but have no kernel inside (consumed by weevil larvae). Pecan weevil damaged pecan are easily recognized by a round exit hole created by the larva (photo at left).

If you spot numerous pecan weevil damaged nuts in your trees this fall, you can be certain that pecan weevil will back with a vengeance in 2013 (pecan weevil has a 2 year life cycle).

Monday, November 7, 2011

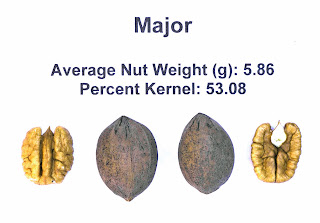

Major's daughters

Over 100 years ago, a seedling pecan tree growing near the confluence of the Green and Ohio Rivers (in Kentucky) was discovered that would become the foundation of this century's most important northern pecan cultivars. Introduced in 1908, 'Major' quickly became known as a disease resistant pecan cultivar that produces quality kernels every year. Today, 'Major' is one of the old standards of the northern pecan industry.

In the years to come, the importance of 'Major' to northern pecan growers may change. 'Major' may become better know as the disease resistant parent of two important cultivars--Kanza and Lakota. Kanza resulted from a controlled cross of Major and Shoshoni, while Lakota has Mahan and Major parentage. Looking at all 3 nuts, you might not suspect Major as being a parent of both Kanza and Lakota. However, Major has transferred excellent pecan scab resistance to both progeny.

The other day I spent some time to inspect the crops held by many of the cultivars we have under test. As usual, our large 'Major' trees (30 yrs-old) had a decent crop of nuts. Just like the old timers say, you can always rely on 'Major' to produce nuts.

I then went on to inspect the crops set by Major's daughters--Kanza and Lakota. After a tremendous crop last year, Kanza has set a fair crop this year (photo at right). Kanza had us fooled most of the year because we didn't see many nuts in the lower portion of the canopy. Once the leaves started to fall, we spotted a good crop of Kanza nuts up in the tree tops. (This is the first indication we might need to thin our Kanza block).

Lakota (photo at left) also set a good crop of nuts in 2011. In fact, Lakota may have produced too many nuts for this drought-stricken, growing season. However, Lakota is like its Major parent. If water becomes limiting, the nuts become smaller but they still produce a quality kernel.

Over the next 10 to 15 years we will learn if the daughters of Major (Kanza & Lakota) become the reliable standards in which northern pecan growers can count on.

In the years to come, the importance of 'Major' to northern pecan growers may change. 'Major' may become better know as the disease resistant parent of two important cultivars--Kanza and Lakota. Kanza resulted from a controlled cross of Major and Shoshoni, while Lakota has Mahan and Major parentage. Looking at all 3 nuts, you might not suspect Major as being a parent of both Kanza and Lakota. However, Major has transferred excellent pecan scab resistance to both progeny.

The other day I spent some time to inspect the crops held by many of the cultivars we have under test. As usual, our large 'Major' trees (30 yrs-old) had a decent crop of nuts. Just like the old timers say, you can always rely on 'Major' to produce nuts.

I then went on to inspect the crops set by Major's daughters--Kanza and Lakota. After a tremendous crop last year, Kanza has set a fair crop this year (photo at right). Kanza had us fooled most of the year because we didn't see many nuts in the lower portion of the canopy. Once the leaves started to fall, we spotted a good crop of Kanza nuts up in the tree tops. (This is the first indication we might need to thin our Kanza block).

Lakota (photo at left) also set a good crop of nuts in 2011. In fact, Lakota may have produced too many nuts for this drought-stricken, growing season. However, Lakota is like its Major parent. If water becomes limiting, the nuts become smaller but they still produce a quality kernel.

Over the next 10 to 15 years we will learn if the daughters of Major (Kanza & Lakota) become the reliable standards in which northern pecan growers can count on.

Thursday, November 3, 2011

Waiting for harvest

Pecan leaves have turned golden yellow and are starting to fall from the trees (photo above). Our pecan shakers are all greased up and the broken fingers in our pecan harvesters have been replaced. In short, we are all ready to start the 2011 harvest season but the nuts just aren't ready yet.

Even though most shucks have been split for several weeks now, we still have too many green shucks to start harvest (photo at right). We could shake our trees today and the harvester would beat off the green shucks but the harvested nuts would be full of moisture. Wet nuts turn into moldy nuts and we can't afford to degrade the quality of the crop just because we are anxious to get the harvest started.

we are anxious to get the harvest started.

If you pull off one of the green shucks, you can actually see moisture trapped between the nut and shuck (photo below right). A pecan will not dry completely until the shuck has turn dark brown and lost all its moisture. A good hard freeze (26 degrees F or below) is what we really need. Cold temepratures would kill the remaining green tissues in the shuck and allow both shuck and nut to dry quickly.

Even though most shucks have been split for several weeks now, we still have too many green shucks to start harvest (photo at right). We could shake our trees today and the harvester would beat off the green shucks but the harvested nuts would be full of moisture. Wet nuts turn into moldy nuts and we can't afford to degrade the quality of the crop just because

we are anxious to get the harvest started.

we are anxious to get the harvest started. If you pull off one of the green shucks, you can actually see moisture trapped between the nut and shuck (photo below right). A pecan will not dry completely until the shuck has turn dark brown and lost all its moisture. A good hard freeze (26 degrees F or below) is what we really need. Cold temepratures would kill the remaining green tissues in the shuck and allow both shuck and nut to dry quickly.

Tuesday, October 25, 2011

Shuck split date and young pecan trees

For northern pecan growers, the date of shuck split is one of the most important cultivar attributes we measure. Pecan cultivars that are well adapted for production in our area, split shucks at least one week before the average date of first fall freeze. Late ripening cultivars usually suffer from poor kernel fill, fuzzy kernels, or "stick-tights" (pecans frozen in the shuck).

In testing new cultivars, we are always anxious to discover the average date of shuck split. However, we have learned to be a little patient before coming to any conclusions about ripening time. In the photo above, you see two clusters of pecans. Both clusters were collected on the same day and from the same cultivar--Lakota. The cluster on the left was taken from a young tree (4 inches in diameter) while the one on the right was taken from a tree 28-years-old (12 inches DBH). In previous posts, I've talked about tree age and drought stress and how pecan trees grow to dominate the landscape. Here is another example of how young trees can differ from mature trees.

Lakota pecans taken from the mature tree have been split for a good two weeks. Note the browning of the shuck near the tips and along the edges of each shuck quarter (pecan on right). In contrast, only one of the 5 nuts in the cluster cut from a young tree shows any signs of shuck split (pecan on left).

Break off the shucks and you can see further evidence that pecans produced by young trees have delayed nut maturity. Full shell color has not yet developed (nut on left) as compared to the pecan collected from the mature tree (nut on right).

It is no wonder why it takes so long to develop and test a new pecan cultivar. Only trees that have grown large enough to "dominate the landscape" provide reliable nut size and maturity date information.

In testing new cultivars, we are always anxious to discover the average date of shuck split. However, we have learned to be a little patient before coming to any conclusions about ripening time. In the photo above, you see two clusters of pecans. Both clusters were collected on the same day and from the same cultivar--Lakota. The cluster on the left was taken from a young tree (4 inches in diameter) while the one on the right was taken from a tree 28-years-old (12 inches DBH). In previous posts, I've talked about tree age and drought stress and how pecan trees grow to dominate the landscape. Here is another example of how young trees can differ from mature trees.

Lakota pecans taken from the mature tree have been split for a good two weeks. Note the browning of the shuck near the tips and along the edges of each shuck quarter (pecan on right). In contrast, only one of the 5 nuts in the cluster cut from a young tree shows any signs of shuck split (pecan on left).

Break off the shucks and you can see further evidence that pecans produced by young trees have delayed nut maturity. Full shell color has not yet developed (nut on left) as compared to the pecan collected from the mature tree (nut on right).

It is no wonder why it takes so long to develop and test a new pecan cultivar. Only trees that have grown large enough to "dominate the landscape" provide reliable nut size and maturity date information.

Friday, October 21, 2011

Harvesting intercrop soybeans

Today we harvested the soybeans planted in our intercrop study. If you've been following this blog, you know that I've described the double-row intercrop system in a previous post and also posted photos of this Spring's soybean planting. Like every field crop planted in SE Kansas this year, our soybean crop suffered from a lack of water. Yield was well below normal for full season beans. The final tally was 23 bushels/acre sold at $11.62/bu.

Thursday, October 20, 2011

Pecan cultivar performance in the Bootheel

Several years ago I started a cooperative pecan cultivar trial with Rick and Cindy Faulkner down in the Bootheel of Missouri. This fall, the young trees in the trial have started to bear a healthy crop of nuts. Pictured at right is a USDA clone 75-8-9 which bore a light crop and showed only a touch of scab. Of all the cultivars under test at this location, Lakota, Kanza, Gardner and USDA 75-8-5 were the first cultivars to bear full crops with nuts hanging throughout the canopies.

I visited the Bootheel in early October and found that Lakota was fully shucksplit (photo at left) at that time. That's great news for SE Missouri pecan growers. It looks like scab-resistant Lakota will be well adapted to the SE Missouri growing season.

Kanza is another scab-free cultivar that is doing well in the Bootheel (photo right). However, an increasing problem facing pecan producers in the Mississippi Delta are the many species of kernel feeding plant bugs that attack pecan. In the photo at right, a leaf-footed bug is feeding on a Kanza nut even at shuck split.

Plant geneticists have created genetically altered cotton and soybeans cultivars resistant to boll worm and pod worm. This has dramatically reduced the amount of pesticides applied to these crops in the Bootheel. However, with fewer sprays, plant bugs flourish and multiply in cotton and soybean fields. When these field crops mature, plant bugs look for alternative plant hosts on which to feed and pecan fits the bill.

I visited the Bootheel in early October and found that Lakota was fully shucksplit (photo at left) at that time. That's great news for SE Missouri pecan growers. It looks like scab-resistant Lakota will be well adapted to the SE Missouri growing season.

Kanza is another scab-free cultivar that is doing well in the Bootheel (photo right). However, an increasing problem facing pecan producers in the Mississippi Delta are the many species of kernel feeding plant bugs that attack pecan. In the photo at right, a leaf-footed bug is feeding on a Kanza nut even at shuck split.

Plant geneticists have created genetically altered cotton and soybeans cultivars resistant to boll worm and pod worm. This has dramatically reduced the amount of pesticides applied to these crops in the Bootheel. However, with fewer sprays, plant bugs flourish and multiply in cotton and soybean fields. When these field crops mature, plant bugs look for alternative plant hosts on which to feed and pecan fits the bill.

Tuesday, October 18, 2011

Drought effects pecan nut shape

Its interesting how our different cultivars react to drought stress in terms of nut shape. To document these changes in nut shape, I've collected nuts from several cultivars then arranged them in order of increasing drought stress.

Its interesting how our different cultivars react to drought stress in terms of nut shape. To document these changes in nut shape, I've collected nuts from several cultivars then arranged them in order of increasing drought stress.Kanza looses its distinctive "tear drop" shape as the prominent nut apex disappears in nuts made smaller by drought. In contrast, the "pinched" apex of Lakota can be recognized regardless of nut size or shape. Interestingly, I found Lakota nuts that had narrow bases and nuts that turned shorter and rounder all on the same tree.

Because Major is a small nut to start with, this year's drought seems to have caused minimal changes in nut shape. Maramec, on the other hand, is a large pecan that suffers greatly from water stress. It is easy to see that Maramec nut size and shape are greatly impacted by lack of soil moisture.

Thursday, October 13, 2011

The Glory of Fall

Pecan trees are not known for brilliant fall color. During normal years, pecan trees hold their green leaves up until the first killing freeze. When the freeze comes, pecan leaves turn brown and fall from the trees almost over night. But this year's drought has changed everything. Pecan trees are shutting down early and putting on a beautiful display of golden leaves.

Wednesday, October 12, 2011

Time for Fall fertilization of native pecan groves

Today we applied 100 lbs.of urea per acre (46 lbs N/Ac) to our pecan grove (photo above). Fall fertilization has proven to be a good way to build nitrogen reserves in native pecan trees, boost yields, and reduce alternate bearing. We generally make this fall application soon after Oct. 1 but wait to time the application to coincide with a rainfall event. This morning, we had a brief shower (.11 inches) so we decided to rush over to the COOP and pick up a load of urea. The ground was still damp when we applied the fertilizer allowing the urea to melt into soil almost immediately.

Next March we will make another fertilizer application but will add potassium to the mix. Our normal Spring fertilizer application is 150 lbs. urea and 100 lbs. potash/ acre (69 lbs. N and 60 Lbs. K).

Thursday, October 6, 2011

2011 Pecan Harvest Walk

Pecan Experiment Field

Tuesday Oct. 11

1:30 PM

When the 2011 growing

season began we originally had planned of holding a full day pecan field day at

the Pecan Experiment Field. And then the hot, dry summer hit. At several times

during the growing season, I was afraid that this year’s pecan crop would be a

total failure. No rain, 100 degree temperatures, and gaping cracks in the soil

all combined to make our trees look terrible. By the end of August I decided

that 2011 was not a good year to promote pecan culture. Area farmers were

disheartened by a dismal corn crop, poor stands of soybeans and a total lack of

forage for cattle. Everyone was worn out by the oppressive heat. So I cancelled

our field day plans.

Fortunately, in

mid-September we had some much needed rain. That one rain event turned a poor

quality pecan crop into a good quality crop. However, by the time things turned

around it was too late to get a full field day put together.

Since we haven’t had this

kind of drought since 1980, I think we have a great opportunity to see how the

numerous cultivars we have under test have fared under drought stress. This year is a good time for a Harvest Walk.

The Harvest Walk will be held at the Pecan Experiment Field, located 2 miles East of Chetopa, KS on US HWY 166 and 3/4 mile south 120th Street. We will be holding this

meeting rain or shine so come prepared for the weather. All are welcomed to attend.

Friday, September 30, 2011

Pecan scab in a dry year

While I was walking over our pecan grove checking cultivars for shuck split, I was surprised to find pecan scab. I thought that a summer of heat and drought would eliminate scab disease from the face of the earth. No such luck! Here is a photo of scab infected 'Giles' pecan tree taken this year. You can see scab lesions (black spots) on the shucks, leaflet midribs, and leaf rachii. Infections on all those plant parts means we actually had multiple scab infection periods throughout the season. How do I know this by just looking at a photo? Here is my thinking.

The scab fungus infects pecan tissues that are rapidly expanding. As new leaves develop in the Spring, the leaf rachis grows rapidity first, followed closely by expanding leaflets. Now look at the photo at right. Note that scab lesions appear on the oldest leaflets at the base of the leaf while the younger leaflets near the end of the leaf are largely scab free. This tells me that we had a scab infection period early in the growing season but as conditions turned hot and dry new scab infections ceased.

So if the hot dry weather stopped the spread of scab, why can I find scab on this year's nut crop (photo at left)? The answers lies in this summer's rainfall events. During the second week of August we finally received some much needed rain. Up until that point, the nuts of most cultivars had hardly grown in size. It was like the trees were waiting for a rain to develop normal sized nuts. When the rains came, we received multiple showers over 6 days. The trees responded with a burst of growth in nut size. The combination of a wet week and rapidly growing nuts provided ideal conditions for the spread of scab. However, since this infection period was so late in the season, the amount of scab observed this year will have little impact on shuck split and kernel quality. But remember, scab will be back next year and we should be prepared to control this important disease.

The scab fungus infects pecan tissues that are rapidly expanding. As new leaves develop in the Spring, the leaf rachis grows rapidity first, followed closely by expanding leaflets. Now look at the photo at right. Note that scab lesions appear on the oldest leaflets at the base of the leaf while the younger leaflets near the end of the leaf are largely scab free. This tells me that we had a scab infection period early in the growing season but as conditions turned hot and dry new scab infections ceased.

So if the hot dry weather stopped the spread of scab, why can I find scab on this year's nut crop (photo at left)? The answers lies in this summer's rainfall events. During the second week of August we finally received some much needed rain. Up until that point, the nuts of most cultivars had hardly grown in size. It was like the trees were waiting for a rain to develop normal sized nuts. When the rains came, we received multiple showers over 6 days. The trees responded with a burst of growth in nut size. The combination of a wet week and rapidly growing nuts provided ideal conditions for the spread of scab. However, since this infection period was so late in the season, the amount of scab observed this year will have little impact on shuck split and kernel quality. But remember, scab will be back next year and we should be prepared to control this important disease.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)