This fall you might have noticed pecan leaves with brown, crispy margins (photo at right). This past summer's rainy weather helped to promote the spread of this disease once known as "fungal leaf scorch". Now, during the month of October, this disease has caused the early defoliation of some pecan trees.

Leaf scorch is actually just one symptoms of a late-season disease called anthracnose which attacks both pecan leaves and nuts. Pecan anthracnose is caused by the fungus, Glomerella cingulata, a common plant pathogen that causes diseases in many fruit and vegetable crops.

On pecan leaves, anthracnose first appears as brown, irregularly shaped lesions along the edges of a leaflet. These lesions can spread rapidly over the entire leaflet ultimately causing early leaf fall. The advancing margin of the infection forms a distinctive dark brown line that separates healthy tissues from disease killed tissue (photo above).

Anthracnose infection of the nut can start as small sunken lesions on the shuck but the disease can spread to cover a large part if not the entire shuck (photo at left). Infections that cover the entire shuck by early August (water stage) can cause smaller nut size and prevent normal shuck split. Anthracnose infections that occur late in season seem to have little impact on the nuts other than to advance the shuck opening process.

To determine the influence of anthracnose on nut quality, I collected nuts with infected shucks, peeled them out, then cut them in half to check kernel fill. The nuts that appear in the photo at right represent a range of anthracnose disease severity--from less disease on the left to the most severe on the right. The nut that came out the the shuck appears directly below the nut-in-shuck photo. Below each nut is that same nut cut in cross-section.

The first thing I notice in the photo is that all 4 nuts are well filled with kernel. Looks like this year's anthracnose infection on nuts will have little effect on kernel quality. However, the nut on the far right was smaller than the others and the shuck did not peel off very easily. In this case, anthracnose probably got an earlier start on colonizing this particular nut.

Even though the kernel inside the nut on the far right looks good, this nut would probably not survive the nut cleaning process. Judging from the force I needed to apply to remove the shuck, this nut would probably be discarded off the cleaning table as a stick-tight. If anthracnose causes enough stick-tights, this disease can lead to significant yield losses.

Anthracnose can be controlled with fungicides and is largely suppressed when we spray fungicides to control pecan scab. However, this year's unusual weather patterns hit just right to promote an outbreak of anthracnose after we finished making fungicide applications aimed at controlling scab.

Wednesday, October 30, 2013

Monday, October 28, 2013

Nut development: 28 Oct. 2013

Each time I checked the development of Maramec nuts this summer, I wondered if they would have enough time to split shuck before the first killing freeze. Well, I got my answer today. I found the shucks split open on our scab-covered Maramec nuts (photo at right).

Splitting shuck before the first freeze is important but remember, Maramec was having a hard time filling out its kernel ever since mid-September. So I collected a few Maramec nuts to check kernel quality. Since scab was also an issue with Maramec this year, I harvested nuts with varying amount of scab infection on the shucks.

The photo above shows four Maramec nuts arranged by severity of scab infection. Below each nut is a photo of that same nut in cross section. Nut "A" had the least amount of scab and achieved normal size for a Maramec. A look inside nut "A" reveals less than perfect kernel fill with air pockets both within the kernel and near the inner-shell partition. The poor kernel fill observed inside nut "A" was a result of this cultivar running out of time and heat to fill the seed. In this case, scab infection was not severe enough to negatively affect kernel fill.

Nut "B" is about the same size as nut "A" but total disease coverage on the shuck of nut "B" has caused even poorer kernel fill. The earlier in the year scab covers the shuck, the greater effect the disease has on nut size. Nuts "C" and "D" are examples of the how nut size can be affected by scab. Early scab infection had the greatest impact on nut "D" decreasing size and severely limiting kernel fill.

Splitting shuck before the first freeze is important but remember, Maramec was having a hard time filling out its kernel ever since mid-September. So I collected a few Maramec nuts to check kernel quality. Since scab was also an issue with Maramec this year, I harvested nuts with varying amount of scab infection on the shucks.

The photo above shows four Maramec nuts arranged by severity of scab infection. Below each nut is a photo of that same nut in cross section. Nut "A" had the least amount of scab and achieved normal size for a Maramec. A look inside nut "A" reveals less than perfect kernel fill with air pockets both within the kernel and near the inner-shell partition. The poor kernel fill observed inside nut "A" was a result of this cultivar running out of time and heat to fill the seed. In this case, scab infection was not severe enough to negatively affect kernel fill.

Nut "B" is about the same size as nut "A" but total disease coverage on the shuck of nut "B" has caused even poorer kernel fill. The earlier in the year scab covers the shuck, the greater effect the disease has on nut size. Nuts "C" and "D" are examples of the how nut size can be affected by scab. Early scab infection had the greatest impact on nut "D" decreasing size and severely limiting kernel fill.

Thursday, October 24, 2013

Pecans ripe but not ready

|

| Gardner, 9 Oct. 2013 |

|

| Gardner, 23 Oct. 2013 |

The bottom line is that the green shuck traps moisture in the nut, preventing it from fully curing. Under natural conditions, our trees will experience a hard freeze, killing the green tissues in the shuck and allowing both shuck and nut to fully dry before harvest.

For those not patient enough to wait for a killing freeze, the nuts can be physically removed from the shuck (by hand or with a mechanical deshucker). Once the nuts are removed from green shucks, they are still full of moisture and will need to be dried. I've see all kinds of methods to air dry pecans. Nuts can be placed in mesh bags and hung from the rafters in the garage. Pecan can also be spread onto drying racks built from 2x4s and 1/2 inch hardware cloth. If you use drying racks, make sure to allow for free air movement from both above the rack and below the hardware cloth bottom. Don't use heat to dry pecans but a simple box fan is useful for keeping air moving around the nuts.

On a larger scale, I've seen growers use a "peanut" wagon to dry pecans. A peanut wagon is basically a large drying rack on four wheels. A grain drying fan (no heat!) is attached to the wagon to keep air moving around the nut crop and promote drying.

Personally, I prefer to allow nature to dry my pecan crop. Natural drying is a heck of a lot less work and doesn't require the purchase of additional equipment or electricity

Labels:

harvest

Wednesday, October 23, 2013

Heavy pecan crop + poor limb structure = limb breakage

The photo at right is a great example of what can happen if a young tree doesn't receive proper training early in its life. This 'Gardner' pecan tree is only 11 years old but was loaded down with nuts. Under the strain of a heavy crop, one large limb simply couldn't support the additional weight and broke from the tree. This tree has now lost nearly one third of its nut bearing area and it will take several years to fill out the canopy again.

A close-up photo of the limb's breaking point reveals exactly why the limb couldn't support a heavy crop load (at left). You can clearly see evidence of a bark inclusion, a key characteristic of a narrow crotch angle. This type of branch attachment is structurally weak and prone to breakage under the stresses of wind, ice, or heavy crop load. In a series of blog posts on training young trees, I give tips on how to avoid growing trees with narrow branch angles by a process I call directive pruning and some simple pruning guidelines I call the 2-foot rule. The training young trees series starts here.

Monday, October 21, 2013

Pecan cultivars ripening by October 21

|

| Greenriver, 21 Oct. 2013 |

| |||

| Giles, 21 Oct. 2013 |

|

| Jayhawk, 21 Oct. 2013 |

|

| Oswego, 21 Oct. 2013 |

| |

| Chetopa, 21 Oct. 2013 |

Thursday, October 17, 2013

Evaluating pecan cultivars in SE Missouri.

|

| Kanza, 17 Oct. 2013 |

|

| Gardner, 17 Oct. 2013 |

| |

| Lakota, 17 Oct. 2013 |

| |

| Surecrop, 17 Oct. 2013 |

| |

| USDA 75-8-5, 17 Oct. 2013 |

|

| Oconee, 17 Oct. 2013 |

Wednesday, October 16, 2013

Broken twigs caused by long-horned beetle

This week, I've been back up in pecan tree canopies collecting nut samples from our breeding plot. When I'm up in the hydraulic lift I get to see things I might not notice from ground level. High-up in one tree, I found a branch that looked like it was cleanly broken in two with the leaves above the break dessicated to a crispy brown (photo at right).

Moving in for a closer look, I found that the branch had a clean break--almost like it was partially cut by a pruning tool. This type of clean break is the tell-tale sign that the limb had been attacked by a long-horn beetle called the twig girdler. You can find a photo of an adult twig girdler and the details of this beetle's life history in a post I made previously.

The female beetle lays eggs in the branch above the girdle. These eggs will hatch next spring and larvae will feed on the recently killed twig. If you find neatly broken off limbs on the ground under your pecan trees this harvest season, it is a good idea to pick up those twigs and burn them to destroy next year's crop of twig girdlers.

Moving in for a closer look, I found that the branch had a clean break--almost like it was partially cut by a pruning tool. This type of clean break is the tell-tale sign that the limb had been attacked by a long-horn beetle called the twig girdler. You can find a photo of an adult twig girdler and the details of this beetle's life history in a post I made previously.

The female beetle lays eggs in the branch above the girdle. These eggs will hatch next spring and larvae will feed on the recently killed twig. If you find neatly broken off limbs on the ground under your pecan trees this harvest season, it is a good idea to pick up those twigs and burn them to destroy next year's crop of twig girdlers.

Monday, October 14, 2013

Nut development: 14 Oct. 2013

|

| Kanza, 14 Oct 2013 |

The photo at left shows the normal progression in shell color development. When the shuck first separates from the shell the sutures are still tightly closed. At this point, the shell is mostly white but marked with the characteristic black speckles and streaks. The first indication of shuck split occurs when a small opening develops at the apex of the nut. As fresh air reaches the shell it oxidizes and begin to turn brown in color (2nd and 3rd nuts in the progression pictured above). As the shucks split downward, from apex to nut base, more air surrounds the shell causing the development of natural shell color. Finally, when shucks are split wide open and the nut inside becomes fully colored.

|

| Maramec, 14 Oct. 2013 |

Kanza seems to be about 10 days later than normal. If Maramec is also 10 days late we'll need freeze-free weather into early November to see shuck split.

I cut into the shuck of a Maramec nut and found no trace of shuck separation at this time (photo at left). The amount of scab on this nut should not impact normal shuck dehiscence so, if and when, Maramec splits open we should be able to record that date.

Sunday, October 13, 2013

Pecan diversity

| ||||||

| Nuts from seedling pecan trees compared to Pawnee (circled) |

The genetic diversity within pecan is amazingly wide. In our breeding plot, we used Pawnee as one of the primary parents in making controlled crosses. In the photo above, I've arranged some of the seedling nuts we have collected that ripen before or at the same time as Pawnee. The two nuts circled in the center of the photo are Pawnee nuts to give you a reference for comparison.

There are a couple of seedling nuts that remind of the Pawnee parent, but the vast majority are drastically different in size and shape. Some of these seedlings will have thick shells while others will be thin shelled. But remember, nut size and percent kernel are just two traits that we need to look at in searching for new pecan cultivars. Disease resistance, good tree structure, and high yield are three major traits are also on the top of my wish list. Its no wonder that new, exceptional, pecan cultivars are so hard to come by.

Thursday, October 10, 2013

Hickory shuckworm: The worm in the shuck.

At this time of year, the shucks on many pecan cultivars are starting to split open. Like every over-anxious nut grower, I can hardly wait to see whats inside the the shuck so I pull a pecan from the tree and peel off the shuck.

In pulling off the shuck, many times I find an area of blackened tunnels carved into the shuck (photo at right). These tunnels in the shuck were created by an insect called the hickory shuckworm.

If you carefully tear away the shuck you can often find the small white caterpillar with a red head that had created the tunnels (photo at left). Even though this insect can tunnel a large portion of the shuck , the early ripening nature of our northern pecan cultivars means kernel filling is largely completed before tunneling becomes extensive. This means late season hickory shuckworm feeding does not pose a serious economic threat in our area.

If hickory shuckworm causes any damage it is usually superficial discoloration on the outside of the shell (photo at right). However, when pecans are mechanically harvested, the constant tumbling inside the equipment usually rubs off all shell markings including shuckworm discoloration.

Once the shuckworm larva reaches maturity, the caterpillar carves a trap door in the shuck (large black spot on shuck at left). The larva then pupates right under the trap door. Once the pupae matures, an adult hickory shuckworm moth emerges from the pupal case and the moth exits the shuck through the pre-made trap door.

The adult hickory shuckworm is a small (3/16") dark moth that has an elongated bell shape when at rest (photo at right). Hickory shuckworm moths are largely nocturnal and you rarely see them during daylight hours. I found this moth resting on the shuck just after it had emerged from the shuck.

In pulling off the shuck, many times I find an area of blackened tunnels carved into the shuck (photo at right). These tunnels in the shuck were created by an insect called the hickory shuckworm.

If you carefully tear away the shuck you can often find the small white caterpillar with a red head that had created the tunnels (photo at left). Even though this insect can tunnel a large portion of the shuck , the early ripening nature of our northern pecan cultivars means kernel filling is largely completed before tunneling becomes extensive. This means late season hickory shuckworm feeding does not pose a serious economic threat in our area.

If hickory shuckworm causes any damage it is usually superficial discoloration on the outside of the shell (photo at right). However, when pecans are mechanically harvested, the constant tumbling inside the equipment usually rubs off all shell markings including shuckworm discoloration.

Once the shuckworm larva reaches maturity, the caterpillar carves a trap door in the shuck (large black spot on shuck at left). The larva then pupates right under the trap door. Once the pupae matures, an adult hickory shuckworm moth emerges from the pupal case and the moth exits the shuck through the pre-made trap door.

The adult hickory shuckworm is a small (3/16") dark moth that has an elongated bell shape when at rest (photo at right). Hickory shuckworm moths are largely nocturnal and you rarely see them during daylight hours. I found this moth resting on the shuck just after it had emerged from the shuck.

Wednesday, October 9, 2013

Pecan cultivars that split shucks in early October 2013

| |

| Pawnee, 9 Oct. 2013 |

And this is the first year we've had a good look at a Stark Bros. pecan cultivar called Surecrop. Photo's of these cultivars are at right and below.

| |

| Gardner, 9 Oct. 2013 |

|

| Faith, 9 Oct. 2013 |

| |

| Peruque, 9 Oct. 2013 |

| |

| Posey, 9 Oct. 2013 |

| |

| Surecrop, 9 Oct. 2013 |

Tuesday, October 8, 2013

Don't judge a pecan by its cover

Over the past several days, I've been in a hydraulic lift collecting pecans from our pecan breeding plot (photo at right). Moving from tree to tree, it is amazing to witness the genetic diversity of pecan. Fortunately, we used early maturing parents for this project and now, 15 years later, most of the trees in this planting have ripened their nuts by the first week of October (not all though).

As you might expect, I have found nuts of all sizes and shapes. Some have thin shells. Some will need a sledge hammer to crack them open. In addition, there are huge differences in reaction to leaf and nut diseases. After looking at so many seedling pecan trees with such diverse sets of cultivar traits, I now have a greater appreciation of how rare it is to find a truly exception new pecan.

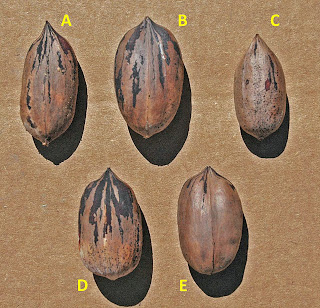

Today, I collected nuts from five different trees just to give you an idea of the type of variation I am seeing in our breeding plot (photo at left). All of these nuts had achieved shuck split with nut "E" probably splitting the earliest. I choose these five pecans because they were roughly the same size in the shuck. When pulling these nuts from the tree, these five nuts appeared to be fairly large. But looks can be deceiving.

In the photo at right, you can see the same five nuts pulled out of their shucks. The differences in size and shape are obvious. A big shuck doesn't always produce a big nut (nut C) and surprisingly large nuts can fall from not-so-impressive shucks (nut E).

The shuck is only the first cover that needs to be peeled back to reveal a pecan's true character. The second cover is the shell. In the photo at left, I've arranged the same five nuts in the same order, but this time, each nut is cut in cross section. Note the differences in shell thickness. Nut "A" has the thinnest shell, while nuts "D" and "C' have heavy shells. Now look at the packing material as it dips down into the dorsal groves of each kernel half. Long narrow dorsal groves means that the packing material might get stuck in the kernel during the cracking process. Nuts "C" and "E" might have a problem in this regard.

Overall nut quality for 2013 looks great. You can look forward to seeing all the nuts we collect this year from the pecan breeding plot on display at the nut exhibits held in conjunction with the KS, MO and IL nut growers annual meetings early next year.

As you might expect, I have found nuts of all sizes and shapes. Some have thin shells. Some will need a sledge hammer to crack them open. In addition, there are huge differences in reaction to leaf and nut diseases. After looking at so many seedling pecan trees with such diverse sets of cultivar traits, I now have a greater appreciation of how rare it is to find a truly exception new pecan.

Today, I collected nuts from five different trees just to give you an idea of the type of variation I am seeing in our breeding plot (photo at left). All of these nuts had achieved shuck split with nut "E" probably splitting the earliest. I choose these five pecans because they were roughly the same size in the shuck. When pulling these nuts from the tree, these five nuts appeared to be fairly large. But looks can be deceiving.

In the photo at right, you can see the same five nuts pulled out of their shucks. The differences in size and shape are obvious. A big shuck doesn't always produce a big nut (nut C) and surprisingly large nuts can fall from not-so-impressive shucks (nut E).

The shuck is only the first cover that needs to be peeled back to reveal a pecan's true character. The second cover is the shell. In the photo at left, I've arranged the same five nuts in the same order, but this time, each nut is cut in cross section. Note the differences in shell thickness. Nut "A" has the thinnest shell, while nuts "D" and "C' have heavy shells. Now look at the packing material as it dips down into the dorsal groves of each kernel half. Long narrow dorsal groves means that the packing material might get stuck in the kernel during the cracking process. Nuts "C" and "E" might have a problem in this regard.

Overall nut quality for 2013 looks great. You can look forward to seeing all the nuts we collect this year from the pecan breeding plot on display at the nut exhibits held in conjunction with the KS, MO and IL nut growers annual meetings early next year.

Friday, October 4, 2013

Time for Fall fertilization

Next March, we'll be back with the fertilizer buggy to make a springtime application of both nitrogen and potassium.

Wednesday, October 2, 2013

A story about resistance to pecan scab

|

| USDA 75-8-5 |

|

| USDA 75-8-9 |

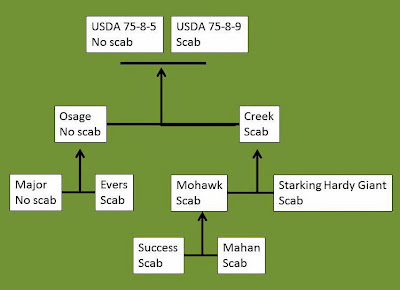

Above is a flow chart of the ancestry of USDA 75-8-5 and USDA 75-8-9. The parents of these clones were the same: Scab resistant, Osage and scab susceptible, Creek. Going back another generation I found that the scab resistance of Osage originated from its Major parent. Looking at the ancestry of Creek, I found scab susceptibility in all cultivars that make up the Creek side of the family tree.

I don't think that scab resistance is a single gene inheritable trait because we see such a wide range of reactions to the scab fungus. However, a quick look at the family tree would lead me to expect that only a portion of Osage x Creek crosses would demonstrate some level of resistance to scab.

Even though 75-8-5 looked scab free in our trials in 2013, this USDA clone has demonstrated only mediocre scab resistance under conditions of high humidity in southern Georgia; a location of much higher scab pressure than SE Kansas (my location).

Tuesday, October 1, 2013

Nut development: 1 Oct 2013

|

| Osage |

|

| Kanza |

|

| Maramec |

I think that Maramec has largely completed kernel fill and you can see that this year's nut quality will be fair to poor (photo at right). The kernel has failed to press all the internal packing material up firmly against the inside of the shell and there are still air spaces near the kernel. You might also note that this Maramec nut is much smaller than normal which can be largely attributed to scab infection. At this point in time, Maramec is not showing any signs of shuck dehiscence. Will we harvest Maramec this fall? It will probably depend on when we get our first hard freeze this fall and if the scab infection will prevent shuck split.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)